Charting A Path Forward - Recommendations & Strategies

As the Western Apache say of their homelands in Arizona, “wisdom sits in places,” and New Mexico is certainly no exception. But one cannot grow wise by simply looking at the surface of the buildings or in neighborhoods. I believe that wisdom can only be achieved by seeing past the layers, which in essence makes it deeply and profoundly contested and connected.

It means thinking about what connects one site to the next as part of a complex and intricate network. Sometimes this is visible and can be mapped, but it can also be found in the flow of the acequia, the profundity of language, music and traditions that linger long after a note has been played, the dust rising ever so slightly from an ancient dance. All of these hold the memory of places, and its people and spirit. But these spaces are also sacred because here is where people have lived for generations, burying their dead, nurturing their young, as well as their minds and their hearts.

In this way, navigating through historic trauma toward transformation will require a roadmap. No matter the direction, it should be expected that making a change of this nature will inevitably cause discord in the community. Making space for peaceful protest is an imperative, however, for civic discourse has always depended upon it for transformation. What follows are some high level recommendations and strategies. Building upon years of advocacy, whether from a film or through direct protest, this work has already begun. The transformative work in the Española and Santa Fe Fiestas are testament to those decades-long and more recent efforts thanks to the courage and commitment to open, honest and moving conversations. But, even there, it is important to recognize that change is a process wherein much more work is required. Beyond these two events, there are many other issues at hand, each requiring perhaps a concerted strategy. In developing some thoughts and ideas as recommendations, we first must recognize the fundamental importance of truth telling and acknowledge historical realities, both of which have framed over time this place we now call New Mexico. We must also identify the values that are core to the communities subject to this report, perhaps utilizing existing structures to do so. Finally, we should be open to continual iteration and prototyping, as this work remains one of process.

Core Values

Core values, like wisdom and memory, are deeply embedded in the world views and structures of traditional land-based communities like those of New Mexico — both Native American and Indo-Hispano — and retaining these values over time, they have governed life, creating balance. Because of the devastation of historic trauma, however, knowledge and wisdom has been lost for some. In this way then, decolonization is about recovery. Santa Fe is still moving through its decision to abolish the Entrada. For some of us who have been working on this for a long period, we recognize that this is only the beginning. What must follow transformation is reconciliation and healing. In this work, it will be critical to develop a process engaging the community to identify core values, to identify the source of those values and to define to what extent these values serve to guide lives. We expect that this individual, heart-centered work will support collective healing.

Theoretical Models and Frameworks

There are certain theoretical models that I have turned to over the years in my work to decolonize, and they remain relevant to this process of transformation, if not reconciliation and healing. The work of Linda Tuhiwai Smith for instance, is definitive in this way. In Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Tuhiwai Smith identifies 25 Indigenous projects that she notes have “derived from the imperatives inside the struggles of the 1970s that placed at the center the survival of peoples, cultures and languages and the struggle to become self-determining, the need to take back control of destinies.” These projects include: Claiming, Testimonies. Storytelling, Celebrating Survival, Remembering, Indigenizing, Intervening, Revitalizing, Connecting, Reading, Writing, Representing, Gendering, Envisioning, Reframing, Restoring, Returning, Democratizing, Networking, Naming, Protecting, Creating, Negotiating, Discovering, and Sharing. Each of these are ideas for change that move toward transformation.

The models identified by Smith are universal, particularly as they are drawn from histories and experiences of the past and across many cultures. There are other models embedded in local wisdom and cultural traditions that are also equally worth examining. I think of the Cochiti Storyteller, a seated clay figurine of a grandmother or grandfather, blossoming with children, with an open mouth, reflecting the active role of telling story. I have always thought of this figure, not only as the embodiment of tradition and creativity, but revealing a profound wisdom and philosophy — a muse relating the collective memory of a community, serving not only to tell story, but revealing the power that narrative holds in bringing community together. I am also reminded of what in northern New Mexico is called la resolana. This place is literally the south side of a building or a plaza, shielded from the wind and bathed in the rays of the sun. What makes this place dynamic is the fact that for generations it has gathered men and women who carefully articulate observations about their contemporary world, relating the memory and wisdom of those that came before them, and creating an open dialogue for what may come. In both of these examples that awaken possibility, the methodology is storytelling and dialogue is pivotal.

Recommendations

In the spirit of imagining reconciliation, I propose the following ideas for consideration:

Moving forward means sometimes acknowledging a wrong, which depends on an apology and the inverse power of rising up and saying, “I forgive you.” History, as well as basic human relations, teaches us that we have to acknowledge harm to move through it. We cannot reverse what happened, but it can be acknowledged with regret. Indeed, transformation requires it.

The fact that Archbishop John Wester took the lead in another major reconciliation efforts is notable. First, on September 12, 2017, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe released the names of nearly 100 priests and religious leaders who were accused or later found guilty of sexually abusing children. With the release of these names, the Archbishop noted, “We must practice openness and transparency whenever possible, as this is essential for rebuilding trust and healing wounds.” The Archbishop also has declared the intention of providing an apology for the historic injustices inflicted by the Church upon Native American peoples of the region. This act of humility is incredibly powerful.

In yet another notable act of humility and courage, in 2015, Anastacio Trujillo, who had himself portrayed DeVargas in 2008, requested and was granted the opportunity to read a prayer from Elizabeth Christine for the Honoring Our Pueblo Existence (HOPE) group at Santa Clara Pueblo, as well as a quote from Pope Francis. On July 9, 2015, addressing the Native peoples in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, the pontiff offered both the acknowledgment and apology in saying:

I say this to you with regret: many grave sins were committed against the native people of America in the name of God. My predecessors acknowledged this, and I too wish to say it. Like St. John Paul II, I ask that the church kneel before God and implore forgiveness for the past and present sins of her sons and daughters. I would also say, and here I wish to be quite clear, like St. John Paul II, I humbly ask forgiveness, not only for the offenses of the Church herself, but also for crimes committed against the Native peoples during the so-called conquest of America.

The reading from Mr. Trujillo revealed his own coming to consciousness and sensitivity to these matters, but even deeper, an understanding of how powerful an apology can be. To have had the insight to invoke this strategy was important.

While these examples demonstrate the impact that this simple act can have, there is more work to be done in this realm of ‘the apology.’

Countering or Cura-ting Context and Counterpoints for Monuments in New Mexico:

While communities across the nation have begun to respond with various strategies, including removal of monuments and other memorials, others have called for providing more context and counterpoint to them. What is done will depend upon the will of the community and perhaps the specific monument or memorial. As a first step, it will be important to identify and map existing monuments in New Mexico. This work was in part begun by the City of Santa Fe, but remains incomplete.1 Heidi Brandow, an artist who participated as a fellow at the Santa Fe Art Institute (SFAI) as part of the SFAI Story Maps initiative, partnered with the City of Santa Fe’s Parks Department, working on social engagement project that examines memorials throughout the city. Her project was to create an inventory of current monuments as well as to categorize them based on demographic information, such as gender and ethnicity. With new maps reflecting the data collected, Brandow’s goal is to include “a proposal that re-envisions the addition of memorials that impart more inclusive and historically accurate representations of the unique and complicated history of Santa Fe.” This project remains salient and important to navigate through the process to address the challenges of monuments.

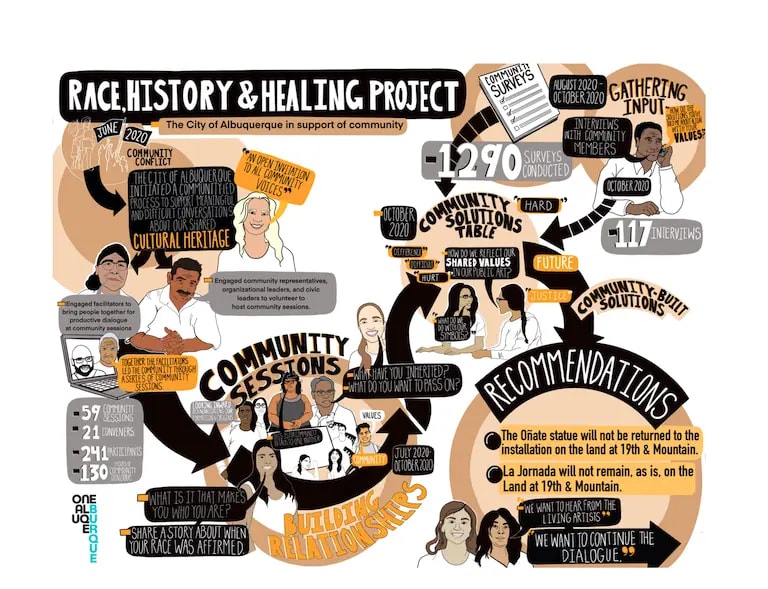

Following the protests that took place in Albuquerque to remove the statue of Juan de Oñate, under the leadership of Dr. Shelle Sanchez, a community engagement process launched that engaged people from across the city. While these processes are never easy, the workhas provided a framework that may be replicable across communities. More about that project can be found at the following link.

Graphic from the project summary, “Race, History & Healing Project - Juan de Oñate Statue Community Dialogue,” 2020.

Graphic from the project summary, “Race, History & Healing Project - Juan de Oñate Statue Community Dialogue,” 2020.Beyond the inventorying of monuments across the state, one strategy would be to follow the work in New Orleans, and begin a process for removal of those monuments that are deemed challenging in a modern era. Making these determinations, may be the work of a commission.

Another strategy would be to curate the monuments as a community engagement effort in combination with media artists to raise consciousness and engender a creative reimagining and critical remembering. By providing an intersection for arts, technology and history, the aim would be to explore the possible transformation of public spaces into forums for inclusion and multiple voices, versus the current singular, static narratives that have produced negative social relations. Toward developing a process for transformation, the work could help test assumptions and identify new paths of public engagement.

Community Engagement Ideas

Resolanas: Indo-Hispano communities throughout northern New Mexico could share information and address internal and often long-standing tensions through Resolanas. This is a potential model for open and transparent dialogue.

While there were many points in Santa Fe’s history punctuated by violence and conflict over the past 300 years, there have also been times of positive convergence and unity reflected in cross cultural marriages, inter-kin networks (comadrazgo and compadrazgo) and friendships. Gathering and disseminating these historic and contemporary testimonies could be profound.

Frigyes Karinthy’s 1929 short story, Chains, first espoused the concept that only six degrees of separation exist between all people; though in spite of the current divisions in our community, I believe there are even fewer separations given of our size. The goal of this project would be to chart that connectivity.

Accentuating Ancestry: In spite of more than a century of accentuating false notions that Native American and Hispano communities are homogenous, they actually share some common ancestors. Revealing this genetic connectivity through a community-wide family tree project would function to create new openings for understanding the past. The work of genealogist and historian José Antonio Esquibel is notable in this regard.

Invite the public to participate in writing a letter from the future. Envisioning themselves as members of the Fiesta Council in five years, writers can reveal how reconciliation led to a Fiesta that brought the community together.

Establish a Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Commission: In response to the contention around the Fiesta, in 2016 I wrote a letter to the editor of the Santa Fe New Mexican, recommending the establishment of a “Santa Fe Fiesta Reconciliation Commission.” Since then, the All Pueblo Council of Governors passed a conceptual framework (December 2017) delineating a five-point plan for formal negotiations regarding the Santa Fe Fiesta, including the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This plan, including the commission, was reaffirmed in a proclamation by the All Pueblo Council of Governors on July 19, 2018.

As noted in the Introduction, when the McCune Foundation originally engaged me to begin to deepen the work of healing and transformation, I submitted a proposal to establish what I called then, the “Santa Fe Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Initiative.” This initiative included the development of what I noted would be a “formalized local, apolitical, nongovernmental entity designed to operate independently and flexibly to identify constructive avenues to facilitate civic trust.”

As the proposal evolved, however, recognizing that this initiative necessarily deserved to be broader than simply Santa Fe, I focused on foundational research, both local and comparative, noting especially the imperative of ‘making the case’ to first assess the viability of a commission, and then to frame the process and action steps. Another step that began, but is collaborative planning also began, but will need to deepen and include community engagement.

With the completion of this research and analysis, including a careful assessment of how these initiatives and commissions have operated in other communities, I have concluded (again) that it would be useful to establish a commission. I recommend that it be broader than Santa Fe and that it emphasize the process, moving first toward transformation, then reconciliation; and if it can be had, healing. Toward this end, I suggest the following steps be undertaken:

Determine Focus and Breadth

Focus and scope of this initiative should encompass a broad geographic area, though initially it could begin more locally.

Develop a Collaborative Planning & Public Engagement Process

While this work already has begun in limited ways, the focus has been narrowly targeted on Santa Fe, although there is also a tremendous amount of work that has begun in Española. To expand, it will be important to explore many more possible collaborations with organizations, institutions and individuals through research and in-person meetings in order to strengthen the capacity and resources. These could include media, education, nonprofits, religious and political partners.

Develop Commission Structure and Objective

While some commissions have been solely located within a government structure, others have been defined through a groundswell in the community. I recommend a combination that is grounded in both grassroots but also actively includes working with government officials in state and local municipalities. This hybrid model can ensure that communities drive the effort and that desired outcomes, to the extent needed, can be implemented through official channels. Further, a mandate must be developed and embraced to the reasoning and broad goals for the commission.

Nomination Process

Once the structure is defined, it will be important to establish a democratic and community-wide nomination process to identify Commission members, including meeting with key stakeholders in advance, drafting public communications and other messaging, offering press interviews, analyzing nominations, and recommending members.