Place

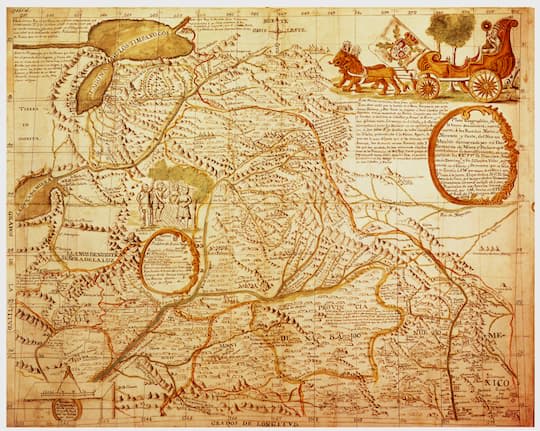

The representations of New Mexico spatially are often revealed in cartography, though in the colonial context, mapping is largely about power and politics: positioning places, people and objects in space; lines on parchment often made at the behest of distant popes, kings and presidents.

The manifest ideology of empire making — Spain, Mexico, the United States — is revealed in the colonial and even modern context, where settlement occurs hand-in-hand with despoblacion, the dis-peopling of an area. Tracing the lure to land, reveals the complexity, perhaps even contradictions of land grants, artist colonies and the economic push and pull of migrations resulting in a contest over space and place that continue in the developments rising up in neighborhoods across the state.

But place, the “first of all beings” according to Aristotle, is a living force and also reflects where wisdom continues to sit, particularly salient where the continuous human habitation on the land is thousands of years old, perhaps beyond time. Even now, when someone looks at a ruin, but sees a home full of laughter and tears, they recognize a deep connection to geographic humanity. Ancient world-views are reflected in Indigenous homelands, though many were diminished or lost by conquest, some have been retained: the four sacred mountains that define the parameters of Dinetah, the Diné homeland; and the Tewa Pueblo Indian world which embody spaces that radiate and reflect balance; surrounding bupingeh (heart of the Pueblo) are the homes and villages, just as nearby hills encircle the community and far off mountains further still, connecting land and sky. I also think of the Spanish word and concept, querencia, more than the love of land, but a generational connection to homeland for Indo-Hispanos who became land-based, peoples who are connected to Indigenous peoples ancestrally and in the contemporary moment, as in-laws, friends and neighbors.

It is critical to understand why and how people settled where they did and how they designed, built and maintained the structures. In this way, the human touch upon New Mexico is visible everywhere; central plazas, churches, villages, burial grounds and agricultural lands all serve as anchors. These lands are intricately connected by trails, roads and acequias, ancient waterways conveying water from the river to fields.

Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, “Plano Geographico, de la tierra descubierta, nuevamente,” 1778.

In all of these spaces, Native American and Indo-Hispano alike, including their points of convergence, villages have sustained multiple changes, including a mix of mud and modernism, where even mobile homes have been converted to reflect a local vernacular.

Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, “Plano Geographico, de la tierra descubierta, nuevamente,” 1778.

In all of these spaces, Native American and Indo-Hispano alike, including their points of convergence, villages have sustained multiple changes, including a mix of mud and modernism, where even mobile homes have been converted to reflect a local vernacular.

The story of place is also about loss, however, of ancestral lands through conquest, governmental seizure, economic necessity and corrupt legal maneuvering, deeply impacting Native American and Indo-Hispano communities in New Mexico.1 The consequence was for many, a shift away from agricultural-pastoral economies, and because of it, these communities have faced declining populations, losing large percentages of their youth to major urban centers in the region, including Albuquerque, Denver, Las Vegas, and Salt Lake City.2 While some families have remained, many more have left, only to return for ritual events (e.g., funerals, weddings or feast days), with untold others never journeying back at all.

What follows are three sections focused on place: Land and Settlement; Land Acknowledgements and the beginning efforts to identity and analyze Site by Site.

Land and Settlement

The broad theme of land and settlement presents an opening for discussing a place-based analysis of colonialism. At one end of this historical arc is the idea of colonial settlement, and at the other, a more contemporary manifestation — gentrification and displacement — that has occurred and continues in neighborhoods across the New Mexico. Layered within, other multiple issues that should be further analyzed, such as land grants.

Settlements

This place we now call New Mexico, is one where the continuous human habitation on the land is thousands of years old. Today, it contains twenty-three Native American tribes, including 19 Pueblos, three Apache tribes (the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, the Jicarilla Apache Nation and the Mescalero Apache Tribe), and the Navajo Nation. While the continuing existence of these sovereign and tribal nations reflect resilience and survival, they also carry the story of displacement. While early records reveal that the migrations and abandonment of certain locales began with inter-tribal warfare, including for instance, when Apache people began settling in and competing with Puebloan peoples for resources. The impact, however, wrought by Spanish conquest was dramatic, shifting the demographics of the land in unprecedented ways. Several colonial expeditions occurred in the early 1500s, including some attempted settlements, though the royally sanctioned expedition led by Juan Oñate in 1598 was definitive.

Recent anti-imperial expressions have interrogated the Doctrine of Discovery, a concept of public international law cited by the United States Supreme Court in a series of decisions, most notably Johnson v. M’Intosh in 1823. In New Mexico, however, the legal precedence of discovery and question began with Spanish law. One of these, the Requerimiento, a 1513 legal doctrine intended as the charter of conquest was in effect until 1556, though its core elements were still in use in the 1598 Spanish conquest of New Mexico.3 Professing a connection to the divine, from God to Pope and Pope to King, and King to himself as a representative, in 1598, Juan de Oñate claimed possession, not only of lands and villages, but of “mountains, rivers, river banks, waters, pastures . . . from the edge of the mountains to the stone in the river and its sands and from the stone and sands in the river to the leaf of the mountains.”4

As the expedition traveled north along the Rio Grande Valley, Oñate paused at each Indian settlement and “obtained” the inhabitants’ formal allegiance to their new king and a new God, revealing of the arrogance of colonialism. Possession was only possible because of dispossession, reflecting the transformational impact of Spanish contact and settlement on Indigenous peoples. According to historian, Dr. Ramon Gutierrez, “of the 134 Indian pueblos that [Juan de] Oñate listed between 1598 and 1601, 43 remained by 1640, a mere 20 by 1707.”5 These numbers reveal that from the moment that all of New Mexico is claimed and settled by a distant king, through to its settlement in the first decade of the seventeenth century, there are manifestations of empire upon ancestral lands.6

The Oñate expedition terminus was at the Tewa village of Ohkay Owingeh, which the conqueror renamed San Juan de los Caballeros; and while it is unknown what sentiments may have actually existed for these early Tewa peoples encountering the expedition, according to Spanish records, they provided hospitality and grace. Their visitors took advantage, occupying the village’s dwellings. Sited at the confluence of the Rio Chama and the Rio Grande del Norte and recognizing a more spacious village, the expedition moved to San Gabriel, making it the first capital of New Mexico. Within the decade, however, the capital would be moved again, south to a site that had once held a Tewa village that can be dated today between A.D. 600 and 1425. Contemporary Native American Tewa communities, particularly Taytsúgeh Oweengeh (Tesuque Pueblo), still recognize this site as Oga Po’oge, White Shell Water Place, though most know it today as Santa Fe.7

By 1620 the provincial capital of La Villa Real de la Santa Fe counted 50 households with approximately 200 residents.8 Within a decade, Fray Alonso de Benavides would report approximately one thousand people in Santa Fe, though by 1638, the population would dramatically decline by 20% due to pestilence.9 Although Santa Fe would remain New Mexico’s only town in in the first decades of the seventeenth century, there were a large number of settlers in haciendas in the lower Rio Grande Valley between Isleta and Senucú in the 1650s. Their numbers remained constant until the 1680 Revolt, with a subsequent census revealing approximately 2,000 settlers.10

Following the Reconquest, La Villa de Santa Cruz de la Cañada, established by families recruited at Mexico City in 1693, became a secondary town for New Mexico. From these two primary settlements, Santa Fe and Santa Cruz de la Cañada, other towns began to radiate out in the early eighteenth century, including Albuquerque, 1706; Belen, 1740; Ranchos de Taos, 1750, Las Trampas, 1751; Ojo Caliente, 1754; and San Miguel del Vado, 1794. However, it is important to recognize, that Spain granted lands already claimed by Indigenous communities. Because the Weminuche and Capote Ute people considered southern Colorado their wintering grounds, along with with Apaches, Comanches, Kiowas and the Diné (Navajo), settlers could not easily establish homesteads in would would become Colorado’s San Luis Valley.

There are two key points to address here. First, an entire field of study, though complicated in a place like New Mexico, has emerged from this notion — “settler colonialism” — defined by a set of features including “asserting false narratives and structures of settler belonging.”11 This leads to the second point.

Even in the colonial period, it is a mistake to assume that these “Spanish settlements” were homogenous. As Linda Tuhiwai Smith has cogently observed, “Europeans resident in colonies were not culturally homogenous, so there were struggles within the colonizing community about its own identity.”12 This was certainly true of the New Mexico settlements from the very beginning, which held Spanish born residents, though castes of mixed bloods, including Indigenous slaves, comprised the bulk of the population.

Neighborhoods - Gentrification

Historic trauma can also be born from more contemporary manifestations of displacements and gentrification is certainly a part of this phenomena of trauma. British sociologist Ruth Glass first coined the term gentrification in 1964 to describe an influx of middle-class people who displaced lower class workers in urban neighborhoods.13 Demographic shifts in the past century and ongoing today in neighborhoods across New Mexico serve as poignant examples of this reality. Gentrification is occurring in large urban areas, like Albuquerque and Las Cruces; in mid-sized cities such as Santa Fe and Taos; but also increasingly the issue is impacting even smaller traditional Hispanic villages including Questa, Trampas, and Chimayo.

For places like Santa Fe and Taos, some of their gentrification history lies in how they developed, with conscious efforts encouraging migration from the outside. In the early twentieth century, for instance, artists living throughout the United States moved to the Southwest, and by the 1920s, both Santa Fe and Taos boasted thriving, nationally-known art colonies. In Santa Fe, urban planning efforts, in conjunction with the real estate industry, proactively established practices and policies to encourage retirees to settle there. More than five decades of promoting a tourism-based economy has also shifted where populations live and what they do.

While gentrification and displacement can be traced to the early part of the twentieth century, it has also been a continual process that continues to exist today. In Santa Fe, some cultural organizations continue to entice new artists to migrate and settle in Santa Fe.

Related to this effort, the concept of“Creative Placemaking,” has become a way to define activities that shape the social and physical characteristics of a place. National thought leaders in the cultural arena, while generally supportive of these activities, have also pushed the field to recognize the “blind spots.” Roberto Bedoya in particular has thought about challenges, writing poignantly, about “a lack of awareness about the politics of belonging and dis-belonging that operate in civil society.”14 As this phrase has been interrogated most recently, another has emerged to replace it—placekeeping, a term that may nuance the reality that people already live in this places, have long since “made them” and have worked for generations to sustain and “keep” them. The unintended consequences of Creative Placemaking can be gentrification and displacement. New influxes of creatives can lead to population shifts that profoundly affect housing affordability, infrastructure, transit and other resources. The historical context or character of a neighborhood or community can be lost and forgotten.

It is important to recognize how patterns of displacement and the forces of gentrification shape communities. The north and eastern parts of Santa Fe, for instance, including its downtown, have responded to a tourism- based model, incorporating upscale dining, retail and cultural entities, resulting in unaffordable, stratified residential neighborhoods. Understanding this broader socio-historical and context — including Santa Fe’s dual history of investment and displacement — is imperative to any effort for sustainable growth, and in particular to address issues of equity.15

These social issues also have impacted rural communities. Today, New Mexico’s rural communities are highly susceptible to poverty, despair, homelessness, high rates of suicide, hunger and drug and alcohol abuse, and as such, often rank at the bottom of many national indicators. These present day realities are bound to something deep and profound, the cumulative impact of transgenerational experiences of displacement and loss, including of knowledge, land and objects.16 It is is critical to recognize that these places have been completely transformed over the past century.

Land Acknowledgements

Although elders taught many, at a young age, including me, to recognize where we stand, upon the layers of Indigenous homelands, even and perhaps especially when those communities have been separated from land that no longer exists. I also learned this from other relatives and friends as an adult during my professional journey. As a graduate student, I was neighbors with Dr. Rina Swentzell, who became a friend and mentor, and speaking to this imperative of homelands, Rina said,“wherever we go, we leave our breath behind us.” For Dr. Swentzell, this powerful invocation recognizes those who came before us and the land upon which we sit, as well as the life force that remains with us as descendants.

Over the past decade, many organizations have begun to adopt the practice of land acknowledgement; some mostly White-led organizations have even developed manuals for doing so. Concomitantly, in the racial reckoning that has swept the nation, protestors have painted with their own acknowledgements, with messages that reads simply, “Land Back”; and in Santa Fe on monuments, buildings and protest signs, “Tewa Land.” These messages also have proliferated on social media. In all of these initiatives, it is important to identify the specific Indigenous communities and to offer a tangible process for reparations.

The imperative underlying this work is to acknowledge Indigenous lands and their people, present and long since gone, to tell the truths about colonial and imperial conquest; but it is also important to recognize the complexity and layers, and to work in community, particularly in those Indigenous communities that do have claims to the lands. Every effort should be made to imagine and develop narratives that effect new openings for understanding and transformation, including a frame for reparations. I had the opportunity to engage in this deep work in collaboration with the Santa Fe Art Institute, culminating in a peopled-land acknowledgment that I drafted based on both archival and ethnographic research, and in consultation with archaeologists, other scholars, and most importantly, in partnership with Tesuque Pueblo. Its members deliberated the document, story gathered around it and ultimately made it their own. This land acknowledgment follows:

Acknowledging this place, its history and its people

We acknowledge the breath of those that came before us and all of the living animals, on the ground and above it. We acknowledge that this place we now call Santa Fe is still recognized as Oga Po’geh (White Shell Water Place). Thousands of years ago, it was a center place for the communities of Northern and Southern Tewa (often identified as Tanos). The living memory and stories told by the people of Taytsúgeh Oweengeh (Tesuque Pueblo) hold profound meaning to this day, revealing that the ancestral site, Oga Po’geh is Taytsúgeh and Taytsúgeh is Oga Po’geh still.

We acknowledge that this place is also part of a much larger sovereign landscape for indigenous peoples: the chronicle of its headwaters are woven into the origin stories of Nambe Pueblo; the clays surrounding the site were a resource for both Tewa people and the Jicarilla Apache; and it is a place where stories are braided into and from the past by the Diné (Navajo), Cochiti, Taos and Hopi Pueblos and more still not yet told.

We acknowledge Spanish settlement occurred over four centuries ago and was as much about the possession of place as it was about the displacement of people. From that beginning, La Villa Real de la Santa Fe was made up of colonists from Spain, Mexico, France, Greece, and Portugal. There were also Africans and many “Indios Méxicanos” whose displacement may have begun in captivity, but lived as free men and women.

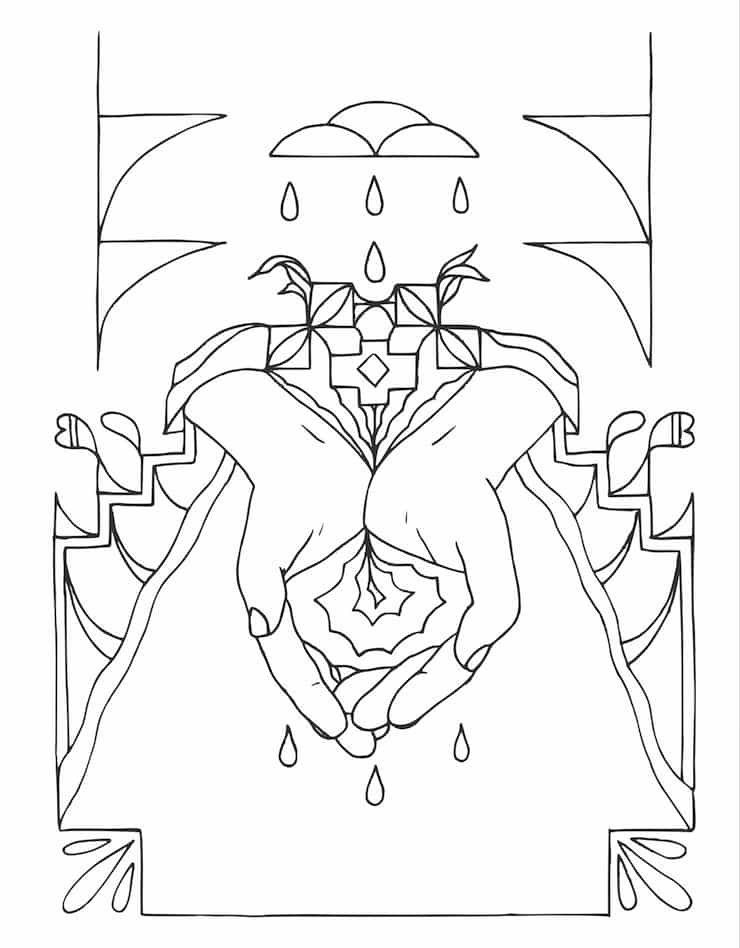

Page from the coloring book developed by SFAI 2020 Story Maps Fellows Diego Medina and Christian Gering.

There were also thousands of enslaved indigenous people who came to be labeled Genízaro, Criado, and Famulo, and whose identities were listed in ecclesiastical records as Aa, Apache, Comanche, Diné, Kiowa, Pawnee, Paiute and Ute. Hundreds more were simply listed in the records as “Mexican Indians.” Complex castas stemmed from these origins, including people labeled as Colores Quebrados, Colores Revueltos, Colores Sospechos, Coyotes, and Mestizos.

Page from the coloring book developed by SFAI 2020 Story Maps Fellows Diego Medina and Christian Gering.

There were also thousands of enslaved indigenous people who came to be labeled Genízaro, Criado, and Famulo, and whose identities were listed in ecclesiastical records as Aa, Apache, Comanche, Diné, Kiowa, Pawnee, Paiute and Ute. Hundreds more were simply listed in the records as “Mexican Indians.” Complex castas stemmed from these origins, including people labeled as Colores Quebrados, Colores Revueltos, Colores Sospechos, Coyotes, and Mestizos.

Two and half centuries after these first Euro-mestizo settlements were formed, the push and pull of migration from every direction has brought new people to this place, including individuals and families from nearly every single state in the nation and from several other countries. The convergence of cultures and the profound and beautiful complexity of identity that is layered across four centuries of presence here, is reflected in the intricately woven genealogies of Santa Fe’s residents.

For those that continue to live in this place, generational or recently arrived, all must recognize the astonishing complexity of this magnificent and sovereign landscape and its people. Acknowledgment also requires holding both the beauty and the pain and supporting ongoing dialogue and story sharing, all of which reflect a vibrant and equitable community. We are the stewards of this land, of its water and air and of each other. Our breath, like the breath of those that precede us, will be left for those that follow us.

Site by Site

Toward understanding the physical manifestations of colonialism, a more thorough analysis of the social-spatial legacy of colonialism remains to be written of New Mexico and the Southwest broadly, including the layout of villages, the presence of churches and the geography of slavery. There are some specific places, however, that represent and reflect contested sites of the colonial history and even violence; yet, even these spaces could be reimagined as sites of consciousness. A few examples follow.

The Santa Fe Plaza

Spanish colonial plazas throughout the Southwest functioned as part and parcel of empire, including a focus on settlement and governance. As noted by historian Ralph Emerson Twitchell, the plaza was at the “center of the city . . .,” and it served as the witness to countless events. He goes on to accentuate some of these events:

Here Onate camped in 1606. Here the Pueblos burned the archives of the province when they rose in 1680. Here de Vargas halted in triumph after his reconquest. Here General Kearny planted the American flag in 1846. There is not an event of importance in the history of the State, from the first coming of the Spaniards to the last few years, with which the Plaza is not intimately connected. In this Plaza in March, 1862, was raised the flag of the Confederate States of America, and the capital occupied by troops belonging to the brigade of General H. H. Sibley.17

Many other events transpired here; some were joyful and loving, others more starkly painful and some more symbolic of the imperial transitions. Recovering history requires an active process of remembering. It demands looking closely at what we see, listening intently to what we hear, distinguishing between the surface and the obscured, suppressed and deeply contested layers. Sometimes it even requires getting close to the ground. In 2006, I was fortunate to be invited by the Santa Fe Art Institute to participate in a community performance piece, “Before You Can Walk: Crawl Santa Fe 2006,” a mass crawl around the plaza, where its participants (myself included) crawled around the plaza with narratives excerpts from Santa Fe’s past (which I scripted) pinned to their backs. It was humbling, but immensely engaging and meaningful. It was a profound act of storytelling that I will not soon forget. Recovery is not simply about recovering from what has been lost, but given the history of colonization in places like Santa Fe, recovery involves decolonization as well. Each of these stories, in effect, demand more than ever, a knowing vigilance that as one layer of imperial gloss may be pulled away, one perhaps even deeper-set still lies on the inside.

The Palace of the Governors

Although recognized today as the Palace of the Governors, it once was known as “Casas Reales de Palacio.” Viceroy Velasco, on March 30, 1609, instructed Pedro de Peralta, the Governor and Captain General of New Mexico, to officially establish the Villa of Santa Fe, drawing upon meticulously detailed colonizing laws that marked out “six vecindades [districts] for the villa and a square block for government buildings.”18 The Ordinances of 1573 provided the parameters for this work, including erecting government buildings to support “the defense and fort against those who would try to disturb or invade the town.” While it is not clear whether the Governor followed the Ordinances, Casas Reales de Palacio did evolve into a fortification.19 Tracing a chronological story of empire and the transitions that define the civil and military authority that resided therein, historian R.E. Twitchell notes that from this building, “Spaniard, Pueblo Indian, then Spaniard again, then Mexican and Pueblo Indian and finally American rulers have held sway and exercised authority over New Mexico.”20

The Palace of the Governors symbolizes different things to different people. It is a structure that is often represented as ‘the oldest continuously occupied government building in what is now the United States,’ and while this may or may not be true, the reality is, it holds tremendous meaning symbolically. It also is, however, a contested site. As historian Dr. Ned Blackhawk has written, “The Palacio’s architecture spoke of dominance and power; but even more eloquent was the macabre decoration hanging in its portal: strings of dried ears of Indigenous people killed by parties commissioned by the governor to punish Indian neighbors.” Tracing the arc of this colonial violence upon the land, Blackhawk notes that not only were these ears taken in battle, but he suggests that the labor of Indian slaves probably prepared these ears for what they would be used, not only as trophy but as sign of the dominance.21

The New Mexico History Museum holds the awesome responsibility of serving as one of the stewards of the State’s history, including one of the most historical assets, the Palace of the Governors. The museum has an opportunity to recognize the layers of history that are embodied in this building, including the intangible stories, and to leverage it as a site of consciousness.

Monuments, Statues and Memorial

Communities across the nation are contending with the existence of monuments in public spaces that reflect historic trauma. At play are not only questions of who owns the past, but also who gets to define where and how history is memorialized.

The subject of power, politics and practices embedded in how history and community memory developed is actually not new. In the post Civil War era, as historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage notes, “white southerners set about codifying their heroic narrative and filling the civic landscape with monuments”; but even then, Black southerners also began to reclaim and develop forms of cultural resistance in memory, though Brundage notes this counter-memory was ignored or remained largely invisible in public spaces.21 Counter-memory included projects of recovery as much as it did those of resistance. It was not until the 1960s, as defined by the Civil Rights Movement, that communities of color began to command a modicum of political power and insist on a more inclusive history, particularly as manifest in public spaces and history curriculums. However, current tensions reveal the little traction gained over the past several decades; and even where some change is evident, the current socio-political landscape reveals how unstable these gains are. With the election of Donald Trump as president, there was a resurgence of a particular brand of nationalism, replete with racism and patriarchy. Communities across the nation responded with various strategies, including removal of imperialist monuments, while others called for providing more context and counterpoint. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, the movement escalated across the United States and beyond, compounded by the death of George Floyd.

Several years ago, I drafted a memorial assessment plan with a three-pronged approach for Santa Fe’s Mayor Javier Gonzales to identify the following: 1) all City dollars that currently support organizations and events celebrating/honoring historic events or people that are perceived as denigrating of any Santa Fe population, past or present; 2) all City property that hold memorials that are perceived as denigrating any Santa Fe population, past or present; and 3) all City streets named after individuals/events that memorialize decimation/denigration of any Santa Fe population, past or present or that are perceived as such.

Despite my encouragement to keep this process moving forward, the current work is a simple static inventory of monuments, murals and other memorials (https://www.santafenm.gov/monuments), and may not necessarily be complete.

There are many monuments throughout New Mexico which draw upon a variety of symbols such as patriarchy, White supremacy, colonization and myth, and a fuller survey and assessment of them is necessary. In terms of mythology, a common sculpture often used to define identity in New Mexico is composed of three stylized busts/heads — an Indian, a conquistador and a cowboy.

Kearney Monument

Activists have focused primarily on Spanish colonial monuments, while those that reflect U.S. imperialism receive less attention. The “Kearney Monument,” which has escaped notice for many decades, is an example. It is yards away from what used to be the towering plaza obelisk and just steps from the Palace of the Governors.

Kearney Monument, Santa Fe Plaza, 1901, Front side of the monument reads: “We come as friends to make you a part of the republic of the United States.” “In our government all men are equal.” “Every man has a right to serve God according to his heart.” Erected by Sunshine Chapter, D.A.R. 1901. Photo by Juan R. Rios, 2016.

Kearney Monument, Santa Fe Plaza, 1901, Front side of the monument reads: “We come as friends to make you a part of the republic of the United States.” “In our government all men are equal.” “Every man has a right to serve God according to his heart.” Erected by Sunshine Chapter, D.A.R. 1901. Photo by Juan R. Rios, 2016.On August 14, 1846, over 2,500 U.S. troops filed into Santa Fe, occupying the territory in what was even then a nationally contested war with Mexico. United States Army General Stephen W. Kearny led the troops, declaring himself military governor and claiming New Mexico as part of the United States. The Daughter’s of the American Revolution erected this modest, seemingly indiscreet monument 55 years later.

The Founding of Santa Fe, Peralta Monument

The Founding of Santa Fe/ Peralta Monument located on Paseo de Peralta and Grant Avenue. Photo by Juan R. Rios, 2016.

Artist Dave McGarity created the “Founding of Santa Fe,” a bronze monument depicting Pedro de Peralta. The third colonial governor of New Mexico, de Peralta served from 1610-1614. Though largely overshadowed by Diego de Vargas Zapata Luján Ponce de León, he nonetheless is considered the founder of Santa Fe.

The Founding of Santa Fe/ Peralta Monument located on Paseo de Peralta and Grant Avenue. Photo by Juan R. Rios, 2016.

Artist Dave McGarity created the “Founding of Santa Fe,” a bronze monument depicting Pedro de Peralta. The third colonial governor of New Mexico, de Peralta served from 1610-1614. Though largely overshadowed by Diego de Vargas Zapata Luján Ponce de León, he nonetheless is considered the founder of Santa Fe.

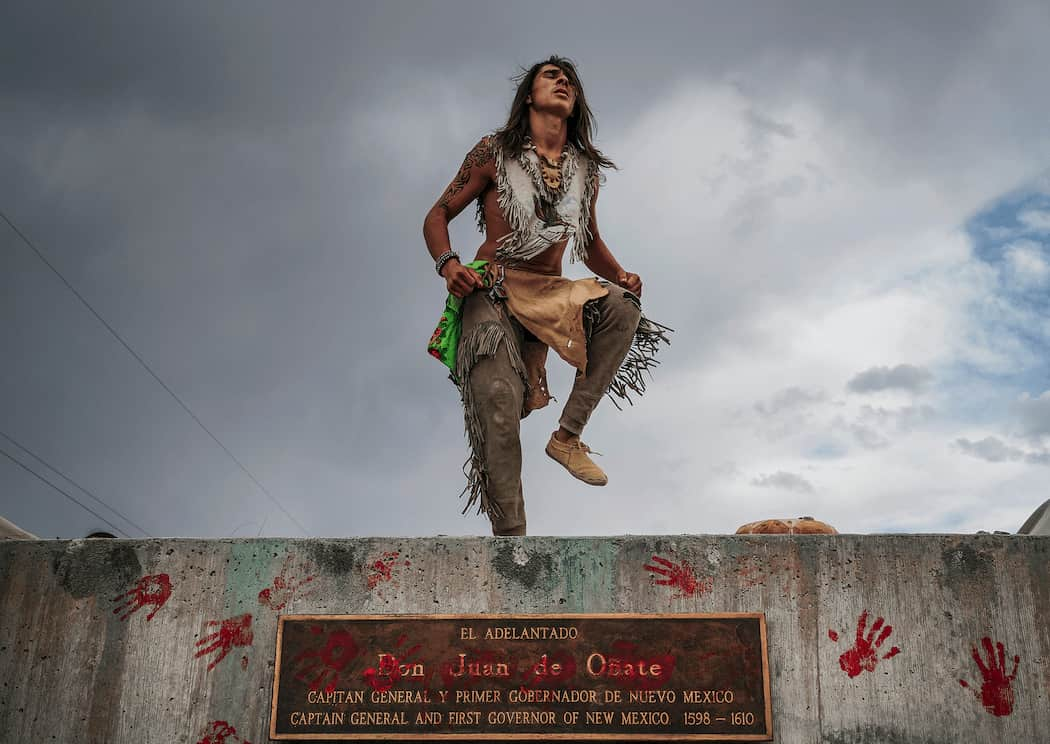

Statue of Oñate

The decade of the 1990s witnessed statewide celebrations of the conquest of New Mexico by Juan de Oñate, considered by some as the founding father of New Mexico, including the commissioning of two statues in his honor, one in Alcalde and the other in Albuquerque. In 2006, the city of El Paso in Texas also installed its own massive equestrian sculpture featuring Oñate at the El Paso International Airport.

Senator Emilio Naranjo, then one of the most powerful politicians in New Mexico, secured $120,000 in 1991 to erect an equestrian statue of Oñate in Alcalde. Sculptor Reynaldo “Sonny” Rivera created the piece, which from its inception, was controversial. As a nod to a sentence passed in 1599 by Oñate against men from the Pueblo of Acoma over the age of twenty-five, in1997, someone sawed off the the right foot of the statue, including spur and stirrup. Thirteen years later, in the second week of June 2020, in response to the the global reckoning over colonialist monuments, a petition began to circulate calling for the removal of the statue, which followed with a planned protest led by Red Nation and other local Indigenous and Hispano groups. Anticipating potential violence, the Rio Arriba County officials removed it. That day, a young dancer, Than Tsídéh, rose up and drawing from the depths of both resilience and a deep remembering, danced on the remaining pedestal, reminding us New Mexicans that we are not museum pieces, that our history is more dynamic than a statue.

Another statue of Oñate has also existed in Albuquerque for decades. The City of Albuquerque commissioned the sculpture of Oñate in the late 1990s. La Jornada depicted the conquistador leading an expedition of Spanish settlers and was installed on the grounds of the Albuquerque Museum. Though there is a detailed history of the piece, fast forward to June 2020, when the city removed it following both a peaceful protest and the violent shooting of a protestor. In the wake of the statue’s removal, the Director of Cultural Services, Dr. Shelle Sanchez, developed and launched a community engagement process that engaged people from across Albuquerque. The purpose of the engagement was to determine what to do about the statue, to either return it to its pedestal or to reimagine the space that it once occupied, differently. More about that project can be found at the this link.

To further raise consciousness about the history of Oñate, I collaborated with Dr. Vanessa Fonseca Chávez to write a short essay and a working bibliography that may be helpful in contextualizing both the sixteenth and the twentieth centuries, bookends of the period in which Juan de Oñate lived and subsequently memorialized.

Obelisk/Soldier’s Monument/War Memorial

In August, 2020, I wrote an essay on this monument, “Centering Truths, Not So Evident” where I detail the history of this monument and provide a roadmap to reimagine it as a the first memorial to Native American slavery. On October 12, 2020, during Indigenous People’s Day, protestors pulled down the obelisk, leaving only a base, which now sits like an abscessed tooth, a wound that will require healing. The essay follows:

Centering Truths, Not So Evident

In the current reckoning with truths about the past — some of which are not so evident — we have an opportunity to examine the symbols placed at the centers of our communities. Towns and cities have long imbued their plazas and squares with meaning, often by placing steel, stone and bronze monuments in public spaces. Many of them have served as instruments of power, glorifying icons of empire and colonial violence, including White supremacy, patriarchy and slavery. The campaigns to erect these pieces also reflect intentional efforts to codify historical memory through mythology, aimed at purposefully harming all those who stood in their shadows.

In this move to raise consciousness and remove these monuments, places like New Mexico seemed to have escaped the attention that is given to locations holding Confederate symbols. It is, after all, a place whose stories have long been marginalized in the national narrative and consciousness, a conquered territory that has never fit into the narrow racial paradigm that has rendered anyone not Black or White invisible. Yet, it is set in a place where Indigenous people have lived continually for millennia and was further settled by Spanish-Mestizos over 422 years ago, older than any settlements that would serve as the “recognized” foundations of the United States.

Given my work as a scholar of Native American slavery and its legacy, there is one monument in particular that has interested me. It is profoundly layered in history and memory, and as such, holds tremendous potential to be reimagined.

The Soldier’s Monument or Obelisk honors the lives of men who died in two intersecting conflicts — the Civil War and the Indian Wars. It is sited at the historic center of Santa Fe, New Mexico, where it was erected less than two decades following the U.S./Mexican War. Founded under the Spanish empire in the early seventeenth century, Santa Fe sits on an ancient site once home to the Northern and Southern Tewa people thousands of years before. The living memory and stories told by the people of Taytsúgeh Oweengeh (Tesuque Pueblo) hold profound meaning to this day, revealing that the ancestral site, Oga Po’geh is Taytsúgeh and Taytsúgeh is Oga Po’geh still.

This memorial is among the oldest placed in this landscape and is built in the shape of an Egyptian obelisk, an ancient symbol representing creation and renewal, particularly in its association with the light of the sun. It was identified with the benu bird, a precursor to the Greek phoenix, but tied to two gods, Thoth, keeper of the records and Ra, the sun god. It is seated upon a raised base, decorated with laurel wreaths symbolizing triumph, held up by four pillars framing inscriptions on marble, one of which has been the subject of contentious civic debate and community activism for decades.

Ohio-born John P. Slough, appointed in 1865 by President Andrew Johnson as the Chief Justice of the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court, spearheaded the effort to build the memorial, which originally intended to focus solely on Union victories in New Mexico. That same year, veterans began placing monuments around the nation, commemorating the Civil War and its fallen heroes. This growing movement inspired Slough, a former colonel of the 1st Colorado Infantry Regiment, the volunteers that participated in the Battle at Glorieta Pass — dubbed the “Gettysburg of the West” — one of two battles fought in New Mexico as a part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the Civil War.

During the 1865–1866 convening of the New Mexico Territorial Legislative session, Slough secured a legislative appropriation of $1,500 for a memorial committee charged to “enclose the graves . . . over the federal soldiers killed at the battle of Apache Cañón at Glorieta and at Valverde” and to “erect one monument or more, at such place or places as they may deem best.” The committee commissioned the architects, John and M. McGee, and eventually granted some of the construction contracts to a firm in St. Louis, Missouri, the city at the other end of the Santa Fe Trail.

A year later, the work on the Obelisk was not yet completed and funding had run out. The legislature appropriated another $1,800, and this time, added a provision requiring commemoration of those individuals fallen in the Indian Wars. Seizing the narrative, members actually drafted into law the precise words to be engraved onto the four marble tablets. One states that the monument was “erected by the people of New Mexico, through their Legislatures of 1866–7–8.” Two others recognize the Civil War battles. The last reads:

To the heroes who have fallen in the various battles with the savage Indians of the Territory of New Mexico

Well before the inscriptions were etched, they were codified and printed in the territorial laws of New Mexico in both English and Spanish. While the English translation used the term, “savage Indians,” the Spanish reflected the more commonly used phrase, “Indios bárbaros.” These terms, racist then and now, reflected a language of imperial relations, and were a part of a much larger vocabulary that effectively classified Indigenous people along an arc between savagery and civilization. It was wording specifically aimed at the Diné (Navajo) and the various bands of the Ndee (Apache) who regularly raided and killed village bound mestizo New Mexicans and Pueblo Indian communities. This representation, however, presented only one side of the story.

From the perspective of the Diné, this period of warfare would be forever imprinted in their memory and language as nahondzod, “the fearing time,” “being chased or herded,” and “under captivity.” While the formerly Hispanos New Mexicans and Diné had long been at war, following the Civil War battles in New Mexico, the U.S. government redeployed the Union Army into smaller and mobile units to wage a war against a different enemy. Commander James Henry Carleton instructed Christopher “Kit” Carson to lead an aggressive campaign culminating in the forced removal of thousands of Diné, marched 300 miles from their homeland to Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River. For those that survived the journey, they would be held from 1864 through to 1868, the same year the Obelisk was finally completed.

Like any site, below the surface are layers of stories, sometimes even underlying texts, and in this case, it is literal. Since the Obelisk was erected, it has appeared as any other memorial of its kind. However, when territorial leaders laid its cornerstone on October 24, 1867, amidst great fanfare that included politicians of both Colorado and New Mexico making speeches, they placed certain items into a time capsule box beneath it. Included were printed copies of the laws of New Mexico codified that year, including the legislation that led to the creation of the monument, as well as an “Act Relative to Involuntary Servitude,” which prohibited and abolished slavery in the territory, even though people would continue to be bound by the institution for many more decades.

Like the monument itself, what was placed at the center of the territorial capital’s plaza and laid below the cornerstone was equally as intentional and imbued with meaning. Among other relics, the time capsule contained two of the nation’s founding documents, the Constitution of the United States and the Declaration of Independence. Much has been written about these documents, including who is privileged, represented or rendered entirely invisible therein. The Declaration of Independence represented Native Americans, for instance, in the singular terms of “merciless Indian savages.” Although, as attested to in the amendments that would follow the original drafting of the Constitution, both of these records were meant to be living documents. Yet, their inclusion at the base of the monument held symbolic meaning for a conquered region and a people who would not gain the rights of full citizenship until 1912 when statehood was finally granted. Even then, though citizenship was finally extended to Native Americans in 1924, Pueblo Indians in New Mexico were not permitted to vote until 1948, 80 years after the cornerstone was laid upon these foundational national documents.

Legislating Legacy

That the Territorial Legislature of New Mexico was interested in the initial proposal to honor the fallen in the Civil War is understandable. Many legislators were directly involved. Kentucky-born William Rynerson served in the Union Army, Company C, 1st California Infantry, which fought to thwart Confederate incursions into the Mesilla Valley of southern New Mexico. The Speaker of the House, Abiquiú, New Mexico-born José Manuel Gallegos, also fought in the campaign against Confederate forces. Among his many experiences was his capture and imprisonment for pro-Union sympathies. Gallegos later served as foreman of a grand jury indicting two dozen New Mexicans for collaborating with the Confederacy. But understanding why the territorial legislature amended the memorial to include those fallen in the Indian Wars requires pulling back another layer of history. Legislator Michael Steck, a Pennsylvania-born physician, served as the Indian Agent in New Mexico from 1852–1863, and then as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs the following two years. He knew all about the intricacies of the Indian Wars. In a journal entry labeled “Synopsis of Indian Scouts and their results for the year 1863,” the day-to-day account records both detail and nuance about the campaign:

M. Steck, Superintendent Indian Affairs, reports that the Utahs have during the last 10 days killed 30 Navajoes, and captured and brought in 60 children of both sexes and captured 30 horses and 2000 sheep. On the 11th inst. four Utahs came in with three scalps and 6 captives. On the 28th the party attacked 150 Indians who fled in all directions, the party here captured 7 children and recovered a captive Mexican boy…; killed 3 Indians and captured 1500 head of sheep and goats; 17 head of horse, mules, burros, and colts. On this scout there were 6 Indians killed, 14 captured, 1 Mexican boy rescued, 1500 head of sheep, 17 horses, mules, burros, and colts captured.

As revealed in this journal, the warfare was multidirectional, but throughout its pages, a phrase appears again and again: “Indian loss unknown.” A year later, in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Steck revealed, from his perspective, the primary cause of the wars.

The Navajos are a powerful tribe, and are noted for their ingenuity and industry. They cultivate wheat and corn extensively, manufacture excellent blankets, and own large herds of sheep. And if properly treated it can certainly be made their interest to cease marauding, and remain at peace in their own country, they have much to lose in the event of a protracted war. They will not, however, be controlled while their children are stolen, bought, and sold by our people….There is no law of the Territory that legalizes the sale of Indians, yet it is done almost daily, without an effort to stop it.

The wars waged against the Diné and others were therefore bound to the institution of slavery and to this day, the legacy and depth of these wounds are simply not known. Steck’s peers knew this truth too, though perhaps differently. The 17th Territorial Legislative Assembly in 1867–1868 included 36 individuals from across New Mexico, and where these men stood regarding these issues mattered. Thirty-three were New Mexican-born Hispanos, one was the son of a Canadian and New Mexican Hispana; two were born in Mexico, one was born in France and as noted above, one was born in Kentucky and another in Pennsylvania. Nearly half enslaved Indians in their own households and another handful were the sons, brothers and neighbors of those who held the enslaved. Some also held poor Hispanos as “peons,” another euphemism for slavery in contention in New Mexico at the time.

Recovering history requires whenever possible to recognize the people, even if only by their enslaved names, which appear in both sacramental and census records. Among the thousands impacted by slavery, those held specifically by these legislators included individuals from villages throughout New Mexico, and include 18 Diné people, three Paiutes, three Utes and 17 others whose tribal affiliations are not recorded. The list of these men, women and children, as grouped into distinct households, follows:

- Ana María, Cornelia, José, Vicente, María de la Cruz, María Refugio, María Guadalupe, María Ramona and Soledad Valdez (home of Juan Benito and Maria Estefana Valdez)

- María Antonia, Juan Manuel, María Rita, and María Archuleta (home of Diego and Jesusita Archuleta)

- María Candelaria, María Dolores, José Antonio, María Guadalupe, José Domingo Apolonio, and Juan Bautista Sandoval (home of Anastacio and Guadalupe Sandoval)

- María de Jesús Baca (home of Severo and Maria Ignacia Baca)

- Gertrudes and Librada Salazar (home of Juan and Carlotta Salazar y Jimenez)

- Juliana Gallegos (home of Pedro and Josefa Gallegos)

- Juan de Jesús Romero (home of Juan Policarpio and Maria Rosalia Romero)

- Guadalupe, María Trinidad, Juan Miguel, María Antonia Jaramillo, José Antonio and Natividad Jaramillo (home of Jose Geronimo and Maria Aniceta Gallegos)

- Ana María Jaramillo (home of Francisco and Nepomocena Jaramillo)

- Gregorio and Guadalupe Esquivel (home of Teodoro and Maria Luz Esquibel)

- Juana, Dolores and Juliana Gallegos (home of Jose Manuel Gallegos and Candelaria Montoya)

- Rosalia Salazar (home of Aniceto and Maria Ignacia Salazar)

- Lucio Aragon (home of Leandro and Eutemia Sanch

- José Antonio Chávez (home of Vicente and María Chavez)

- María Juana Otero (home of Gregorio N. Otero)

In total, nearly half of the 36 legislators held up to 41 enslaved people, though Juan Benito Valdez, would be remembered in stories shared during the New Deal Writers Project as enslaving himself as many as 30 individuals. In ensuing unsuccessful efforts to end Native American slavery in the region, Valdez and colleague Juan Policarpio Romero, would be charged with the crime of slavery, along with hundreds of others in Taos, Santa Fe and Rio Arriba Counties. In the end, the grand jury that heard the cases failed to indict, not surprising since its composition were citizens intricately bound to the institution of slavery.

Reimagining the Memorial

The Obelisk has been the subject of debate and protest for decades. At the heart of the controversy is the racist word “savage,” which a protester chiseled out in 1974; others inserted different words through the years: “courageous,” “resilient,” and “our brothers.” Yet time has revealed, even in the near five decade absence of the word, the harm lingers.

Red Hands on the Obelisk, Santa Fe, New Mexico, June, 2020. Photo courtesy of Juan. R. Rios.

Red Hands on the Obelisk, Santa Fe, New Mexico, June, 2020. Photo courtesy of Juan. R. Rios.

While most people continue to conflate the issue and identities into simple binaries, doing so reifies the falacy and is deeply harmful. Untangling these issues is not easy, especially in a region where the culturally and genetically interconnected Native American and Indo-Hispano communities have all inherited the legacy of colonialism and both feel a sense of loss. Ironically, for the contemporary Indo-Hispanos of Santa Fe, who have been disproportionately impacted by loss of land, language and traditions, and who have experienced the dramatic effects of gentrification in a place their ancestors have lived for centuries, the removal of this and other monuments feels like one more thing being “taken away.”

Recently, building off of the work of activists of previous generations of Native Americans and Chicanos alike, Three Sisters Collective, an organization focused on “Pueblo womxn centric arts, activism, and empowerment,” called for the dismantling of this and two other monuments in the city. In the face of the growing global movements as well as local pressures to remove these public symbols, the City’s mayor, unilaterally announced they would be removed; and working overnight with State employees, moved to do so, though only succeeding in breaking off the Obelisk’s tip. Given questions over the jurisdiction and the legality of dismantling the monument, its fate currently remains unknown. It was recently defaced with red paint, hand prints and messages of protest, and the offending tablet broken. Santa Fe’s Arts and Culture Department Director Pauline Kanako Kamiyama has issued a call for artists to contribute art work for a plywood surface that is temporarily covering the base.

Given the full and layered history of the Obelisk, I believe in a collective and creative capacity to reimagine it to generate dialogue and deepen consciousness about the past. More than any other memorial in this landscape, it holds tremendous potential to re-present history and memorialize those impacted by slavery, either fighting against its spread or those fallen victim to the experience, albeit another, different slavery. While I believe some monuments should come down because their existence is indefensible, embodying in single individuals the stories of domination, I contend this one should remain, but necessarily evolve.

Toward this end, I offer the following ideas and elements that may serve as inspiration for a renewed installation.

Remove and Contextualize the Offensive Tablet

The marble tablet with the offensive inscription should be removed. It could be curated to contextualize how the language of colonialism was, as Antonio de Nebrija reportedly said to the fifteenth century Spanish Queen Isabella, “an instrument of empire.” In this way, it could serve to open dialogue about how words like “savage” and “bárbaro” exist as part of a larger vocabulary that wounds

I generally do not believe in the argument that these monuments “belong in a museum,” if for no other reason, because of their sheer volume, scale and scope. However, this one piece could serve as a prototype but should be installed at the Roundhouse, the capitol building for the State of New Mexico. The use of the language was developed by that political body in 1867 and the current State Legislature has the opportunity to create space for this important dialogue to move forward.

Incorporate a Peopled-Land Acknowledgement

Develop and design an acknowledgment that this place now called Santa Fe is still recognized as Oga Po’geh (White Shell Water Place) and thousands of years ago, it was a center for the communities of Northern and Southern Tewa (often identified as Tanos). The living memory and stories told by the people of Taytsúgeh Oweengeh (Tesuque Pueblo) reveal the profound meaning held by this site to this day. In this, it should also be acknowledged it is part of a much larger sovereign landscape for Indigenous peoples: the chronicle of its headwaters are woven into the origin stories of Nambe Pueblo; the clays surrounding the site were a resource for both Tewa people and the Jicarilla Apache; and it is set in location where stories are braided into and from the past by the Diné (Navajo), Cochiti, Taos and Hopi Pueblos, with more still not yet fully told.

Deepen the Civil War memorial

The names of those who fought in the war against the spread of African American slavery are invisible, not only from the national narrative and consciousness, but from local memory. Recovering and elevating them, which would include people from Colorado and New Mexico (both Indo-Hispano and Native American Pueblo individuals), should be added into this memorial.

Design a Memorial to the Enslaved

The Indian Wars impacted multiple communities, but those that were most violently caught in the middle and yet the most obscured were those that were captured and bound by the institution of another slavery.

Earlier in this essay, I identified the names of those held in the homes of the legislators, but these are but a small fraction of the thousands enslaved in the region, including those labeled in sacramental records as Aa, Apache, Comanche, Diné, Kiowa, Pawnee, Paiute and Ute. There were also Africans and many “Indios Méxicanos” whose displacement may have begun in captivity, but lived as free men and women.

Using this center-space to create the first ever memorial to the enslaved Native Americans would be monumental. Contemporary identities stem from these origins, and this profound and beautiful complexity is layered across four centuries of presence, reflecting an intricately woven genealogy that inhabits contemporary Santa Fe Nuevomexicanos and beyond. Some potential elements of this memorial could include:

A Reflecting Pool

Set in contrast to the stone, the element of water would become part of the land acknowledgment set upon white shell to provide an opportunity for reflection literally and figuratively. Santa Fe has become a place where its generational residents can no longer see themselves reflected. Even if the stories of the enslaved have been quieted over the years by whispers as much as by silence, hushed aside even by those who have inherited the story — carrying, as it is, if not its geography in their faces and hands, certainly its memory exists in an aching consciousness. The fence that currently surrounds the monument could come down and a space encircling the monument could be engineered to become a reflecting pool, even if not with actual water, then perhaps a creatively designed metaphor.

The Names

Based on my database of thousands of the enslaved, I would work with a media artist/projectionist to create an installation highlighting a revolving list of those names that could be projected onto the pool and the obelisk. More than names, these are the ancestors of contemporary Indo-Hispanos of the region.

While this monument sits in America, that America is set in an ancient and sovereign landscape, where deeply meaningful physical and spiritual elements intersect at the center of Native American Pueblo communities. In these Indigenous worldviews, there are actually multiple centers, radiating out, revealing profound and deep spiritual and cultural connections. Set in this context, a profound and beautiful complexity of identity is layered across four centuries of presence here, giving birth to the intricately woven genealogy that inhabits contemporary Santa Fe Nuevomexicanos. What we place at the center of our towns and cities matters; and over the past several decades, scholars, artists, community leaders and others have actively worked to account for the cultural wounds that resulted from colonial violence and to illuminate the difficult truths about the past, in part by advocating for the removal of harmful monuments. The fact that this one in Santa Fe, originally inspired by an ancient symbol tied to illumination and records, is all the more profound. Layered over a founding document that speaks to holding certain truths to be ‘self-evident,’ a reimagined Obelisk has the potential to reveal underlying truths at the heart of this community and ultimately, to begin envisioning a site of consciousness that opens the possibility for racial healing and reconciliation.

Post-Script: While the Santa Fe Mayor, Alan Webber, publicly promised in June 2020 to initiate a civic process that would culminate in the removal of the Soldier’s Monument in June, he seemingly failed to launch this effort and compounded the situation by a lack of transparency and community engagement and communication. Four months later, on October 12, Indigenous People’s Day, activists occupied the site, chained themselves to the monument, and eventually pulled it down, leaving only the base. In the aftermath of the destruction, the city covered the base in plywood the mayor announced he would work to launch a process and commission to address the tensions in the community. To date, the Culture, History, Arts, Reconciliation and Truth Committee (CHART), has not yet begun. While the monument has been destroyed, the effort to reimagine the site remains as important an imperative as ever.

Notes:

For how these imperial policies and practices impacted Indigenous peoples in the Southwest, see Edward H. Spicer, Cycles of Conquest - The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on Indians of the Southwest, 1533-1960 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1981). In violation of the “Treaty of Guadalupe de Hidalgo,” vast amount of lands were lost in the Hispanic community because of takings by federal government and through legal maneuvers. For an overview of this, see Malcolm Ebright, Land Grants and Lawsuits in Northern New Mexico (Santa Fe, N.M.: Center for Land Grants Press, 2008). ↩︎

For this history see, Sarah Deutsch, No Separate Refuge: Culture, Class, and Gender on an Anglo-Hispanic Frontier in the American Southwest, 1880-1940 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). ↩︎

Williams, The American Indian in Western Legal Thought, pp. 88-93. ↩︎

See George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, eds., Don Juan de Oñate: Colonizer of New Mexico, 1595–1628(Santa Fe: Patalacio, 1927; rpt., Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1953). Marc Simmons, The Last Conquistador: Juan de Oñate and the Settling of the Far Southwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991). The act of possession is also printed in Gaspar Perez de Villagra, Historia de la Nueva Mexico, fols. 114-132. ↩︎

See Ramon A. Gutierrez, When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991, p. xxviii. See also Albert H. Schroeder, “Pueblos Abandoned in Historic Times,” Handbook of North American Indians: vol. 9, pp. 236-54. ↩︎

Pedro de Peralta, New Mexico’s second colonial governor, is given viceregal instructions in 1609 to establish the villa, but even today, beneath the modern city lay the remains of a village including gardens, middens, and wall footings delineating houses dating from between A.D. 600 and 1425, a place that contemporary Tewa communities still recognize as Po’oge (White Shell Water Place). See Frances Levine, “Down Under and Ancient City: An Archaeologist’s View of Santa Fe,” in Santa Fe: History of an Ancient City, ed. David Grant Noble (Santa Fe: School of American Research, 1989, pp. 9-25. Also see White Shell Water Place: An Anthology of Native American Reflections on the 400th Anniversary of the Founding of Santa Fe 2000, ed. F. Richard Sanchez, with Stephen Wall and Ann Filemyr. ↩︎

Also see White Shell Water Place: An Anthology of Native American Reflections on the 400th Anniversary of the Founding of Santa Fe 2000, ed. F. Richard Sanchez, with Stephen Wall and Ann Filemyr. ↩︎

Communication from Viceroy to King, May 27, 1620 in George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, eds, and trans., Don Juan de Onate: Colonizer of New Mexico, 1595-1628 (Albuquerque: 1940). pp. 1139-40. ↩︎

Peter P. Forrestal, trans., Benavides Memorial of 1630 (Washington, D.C., 1954). pp. 23-24. For 1638 decline see Petition of Fray Juan de la Prada, September 26, 1638 in Charles W. Hackett, ed. and trans., Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, 1773 (Washington, D.C., 1937), vol. 3. p. 108 ↩︎

Muster Roll, September 29, 1680, in Charles W. Hacket, ed., Revolt of the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico and Otermin’s Attempted Reconquest, 1680-1682 (Albuquerque, 1942), vol I, pp. 134-53. ↩︎

See https://globalsocialtheory.org/concepts/settler-colonialism/ ↩︎

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books Ltd, 1999), p. 23 ↩︎

Ruth Glass, London: Aspects of Change. (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1964). ↩︎

Roberto Bedoya, “Placemaking and the Politics of Belonging and Dis-belonging,” Published in GIA Reader, Vol 24, No 1 (Winter 2013). ↩︎

Understanding this broader socio-historical context, including Santa Fe’s dual history of investment and displacement is imperative to any effort for sustainable growth, and in particular to addressing issues of equity. These shifts are much more delineated in Equitable Development and Risk of Displacement, a report authored by Human Impact Partners with collaboration from Chainbreakers Collective and NM Health Equity Partnership. For the full report, see https://chainbreaker.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/HIA-report-Final.pdf ↩︎

While there is a large amount of research on present day realities facing communities of color, the efforts to link this to historic trauma has only begun. There are several studies that have emerged toward this end, however. Taos County has the highest rates of opioid use in the State of New Mexico and Professor Sherman makes a direct correlation between this particular issue and historic trauma for Taos. See Dana K. Sherman, “Opioid Overdose in Taos, New Mexico,” The Journal of Global Health, April 1, 2017 http://www.ghjournal.org/opioid-overdose-in-taos-new-mexico-2/ See also, Goodkind,J.,Hess,J., Gorman, B., and Parker,D. (2012). “We’re Still in a Struggle”: Dine Resilience, Survival, Historical Trauma and Healing. Qualitative Health Research, 1019-1036. ↩︎

Ralph Emerson Twitchell, Leading Facts of New Mexico History (Cedar Rapids: The Torch Press, 1917) pp. 16-17. ↩︎

See Irineo L. Chaves, “La Ynstuccion a Don Pedro de Peralta (1609),” transcribed from the Archives of the Indias at Seville, Spain by Lansing B. Bloom, with translation. New Mexico Historical Review, vol. 4, (2): 178-187. ↩︎

For more detail about the Palace of the Governors see Cordelia Thomas Snow, “A Brief History of the Palace of the Governors and a Preliminary Report of the 1974 Excavation,” El Palacio, Vol 80, No. 3., 1974. ↩︎

Twitchell, Leading Fact of New Mexico History, Vol. IV, p. 12. ↩︎

See W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory, Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005, p. 10. ↩︎