Time

Temporally, New Mexico has often been divided by archaeologists into the troublesome binary of “prehistoric” and “historic”; or framed by historians into distinct periods: “Pre-contact, Spanish Colonial, Mexican, Territorial and American.” All fail to capture the complexity of cycles and the transitions that lead up to and follow events, both cataclysmic and ordinary.

Time here, perhaps anywhere, cannot be captured in a straight line, but rather in the symbol of a spiral and the radiating circles of cause and effect. Sometimes words, phrases or entire stories were more revealing than numbers, like emergence or words like Ha’atastín, the Diné representation of a period remembered as “watching out for enemies.” Yet among the countless dates, there are many that hold meaning still: contact and settlement — 1539, the moment of first contact at Halona:wa Idiwana, the Middle Place, present-day Zuñi Pueblo and 1598, the date of Spanish settlers arriving in New Mexico; revolutions, including that of 1680, the most successful Indigenous uprising in what is now the U.S. and one that would ensure survival and rescript Pueblo-Spanish relations, or that of 1847, defined by a coalition of Pueblo and Hispanos who would rise up against U.S. imperial occupation; belonging, 1912, the date when New Mexico shifted from a Territory to a State, following over six decades of denial of full citizenship to its residents because of race and religion. In the century since this last transition, a chain of events would transpire — the rise of the military industrial complex, the building of a bomb, the establishment of internment camps and continual struggles over civil rights.

New Mexico is indeed delicate, changing, but there are always lessons and still there is joy, but it may not lie in the grand or epic, but instead within common cycles, celebrations and ceremonies: dust rising from dances that have persisted for ages, language and prayer that rise and fall like a song, fingers moving over rosary beads; the births and anniversaries that have resulted from love; the dignity of work, including the annual rituals of cleaning the ditch, harvesting the crops or the daily acts of simply preparing and sharing a meal.

From the beginning of time, people have gathered together to commemorate. These events, may have begun organically with the passing of an elder or the birth of a child, celebrating a harvest or marking the beginning or end of a migration. Some of these gatherings are one time events. Others evolved into traditions, defined by a recurrence from generation to generation, some emerging organically, others intentionally invented, defined by a range from factually authentic to wholly imagined and fabricated.

Past Commemorative Events

There are various temporal distinctions that have been employed to understand history. These divisions reify the Nietzschean idea of a monumental approach to history, emphasizing static-singular events, without considering context or cause and effect. In this approach, there is a failure to understand that history is dynamic. Celebrating an anniversary, for example, in and of itself is not the issue; but when a date is “frozen” (e.g. 1598, 1680, 1837, 1848, 1912) — as if the people and places that made and make possible the celebrated event do not evolve — the understanding and representation of history is limited and problematic.

People shape the representations of the past. Understanding how the commemorative events of the twentieth century came to be defined by language, symbols and narratives requires recognizing how the demographic profile began to shift as part of the imperial transition from Mexican to American rule. Even more revealing, however, was the growing Anglo domination of political and economic power. As historian Charles Montgomery discovered, “At the turn of the century the newcomers controlled the territory’s new railroad and mining industries, its law firms and banks, and its largest newspapers. Anglos led both political parties and constituted virtually all federally appointed officials.”1 As Anglos concentrated their power, they largely shaped celebrations.

People shape the representations of the past. Understanding how the commemorative events of the twentieth century came to be defined by language, symbols and narratives requires recognizing how the demographic profile began to shift as part of the imperial transition from Mexican to American rule. Even more revealing, however, was the growing Anglo domination of political and economic power. As historian Charles Montgomery discovered, “At the turn of the century the newcomers controlled the territory’s new railroad and mining industries, its law firms and banks, and its largest newspapers. Anglos led both political parties and constituted virtually all federally appointed officials.”1 As Anglos concentrated their power, they largely shaped celebrations.

This context explains the historical antecedents, a mindset and pageantry that developed the present day Fiestas in Española, Santa Fe and Taos. Three events particularly offer a glimpse of what these commemorative events in New Mexico looked like in the past.

It is this context which is necessary in order to understand the mindset and pageantry that developed toward present day Fiestas in Española, Santa Fe and Taos. It defined, however, the historical antecedents and how the celebrations of fiestas developed. In what follows, are three events that give us a glimpse for what these commemorative events in New Mexico have looked like in the past.

Tertio-Millennial Celebration

In 1883, when the railroad bypassed the city of Santa Fe, a group of community leaders — 12 Anglo men and one sole Hispano — created an anniversary celebration to attract business investments and tourism.2

The 1883 Tertio Millennial Exposition was a forty-five day extravaganza commemorating 333 years of European settlement in Santa Fe. Historian and Santa Fe native, Charles Montgomery, wrote about this event:

The organizers knew perfectly well that the first official Spanish colony was established in 1598, not 1550, and that Santa Fe was not founded until 1610. But none of that really mattered. To draw the attention of eastern newspapers, they chose a date that justified an elaborate commemoration, complete with a rousing, if chaotic, potpourri of historical costumes and tableaus. The only resemblance of historical coherence came in late July, when organizers staged a trio of historical pageants, each of which was meant to recall the dramatic events of a single century. On the first two days, richly attired Spanish conquistadores and Franciscan priests shared the stage with Apaches, Zunis, and Pueblos. Day three, featuring the coming of American soldiers, brought spectators up to the modern period.3

The celebration failed on many levels, including financially, where, according to Montgomery, it did not attract the desired capital investments and tourism, which was looming, but yet not fully developed. The inclination of the organizers to leverage culture, including history and the arts, was a good one; however, the failure came from a lack of imagination and the alignment of values that placed the residents of the community at the forefront.

Aside from a temporal frame that was completely falsely constructed, organizers also drew upon stereotypical representations of both Hispano and Native Americans depicted as static and frozen in time. This wholly fabricated extravaganza embodied the elements of all those events that would follow, including forefronting a celebration of conquest — including conquistadores as icons — and using static moments. Though Anglo power brokers largely invented the event, elite Hispanos relished the narrative, and even portrayed the roles. Felipe Delgado, for instance, proudly depicted Francisco Vázquez de Coronado; and Major José D. Sena, “attired as a Spanish Chieftain,” characterized the conquerors and “their descendants here gathered” as “Spaniards.”4 Thus, the selective elements of the past, firmly established, would be further solidified in the decades to come.

1940 Coronado Cuarto Centennial Exposition

Six decades separate the 1940 Coronado Cuarto Centennial Exposition from the Tertio-Millennial celebration. In another effort to increase tourism, state officials began to design a campaign in 1931 that culminated in a statewide tribute to the conquistador, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado. At the center of the commemoration was the Coronado Entrada, a colonial expedition led by Coronado from Compostela, México into present-day Kansas and through parts of the southwestern United States. A series of pageants performed on an enlarged mobile stage that toured throughout the state framed the event. Unlike the previous 1883 exposition, the Coronado Cuarto Centennial successfully drew tourists.5 As was true of the 1883 event, organizers decided to ignore the facts of Coronado’s devastating and deadly impact upon the Pueblo village of Tiguex. Instead, they painted a narrative picture of a heroic and noble colonizer, and as one promotional guide noted, formed “the basis for the European civilization in the Southwest.”6 Although the decision to celebrate Coronado was driven by the date, it was at the expense of commemorating the figure of Estebanico, the African whose explorations had preceded Coronado. Even as the commemorations were taking place, African American scholar Rayford Logan argued that Esteban had “discovered” New Mexico, and the decision to exclude him and instead promote Coronado was driven by racism.7

A stamp commemorating the Coronado Cuarto Centennial from 1940

A stamp commemorating the Coronado Cuarto Centennial from 1940As this selective and discriminating narrative began to unfold through the decades in these events — with many non-native Anglo men involved — several Hispano supporters primarily from “elite” families began to buy into this tale, including Coronado Cuarto Centennial Exposition Commission Secretary, Gilberto Espinosa, B.C. Hernandez, Concha Ortiz y Pino and Fabiola Cabeza de Baca. The Coronado Cuarto Centennial however, did, have its progressive detractors, including folklorist Arthur Campa, who throughout the 1930s criticized the fixation on Spanish origins, particularly at the expense of Indigenous and Mexican influences. Ahead of his time, in 1939, Campa became even more aggressive in his critique of Spanish heritage symbolism. In a series of essays in El Nuevo Mexicano, the Spanish language press, this young scholar called on his colleagues to recognize several key issues, including the fallacy of purity of blood and the erasure from the story of Indigenous and Mexican ancestors.8 In 1940, the same year of the Exposition, education professor, George I. Sánchez, published his critical study of Taos County, Forgotten People, which documented the impact of Anglo conquest and neglect after 1848. Like Campa, Sánchez critiqued the celebration as organized by outsiders who ignored not only the knowledge and local customs of the people, but also the issues most impacting them.9 Isleta Pueblo Governor and President of the All Indian Pueblo Council, Pablo Abeyta, also critiqued the event, calling into question the honoring of a man who had killed Pueblo people and forced them into war.10 The resistance and efforts to raise consciousness by Campa, Sánchez and Abeyta fell on deaf ears and the celebrations went on.

Columbus Day and the Columbus Quincentenary

The United States celebrated the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas on October 12, 1492 at key anniversary moments, including 1792, 1892, and with the most recent quincentenary in 1992. While the first statewide celebration took place in 1905 in Colorado, it became a federal holiday under the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration in 1934, in an era largely marked by commemorative practice. In 1892 in New Mexico, the local press ran stories in Santa Fe, Silver City, Las Cruces and Las Vegas, the latter of which referenced Columbus as the “greatest educator,” and invoking sentiments of manifest destiny, declaring “he taught mankind that human destiny extends over the whole world.” As noted in the paper, the celebration was to “bring together the school children, in the country, in the same hour, to commemorate the greatest event in the modern world.”11

Fast forward nearly one hundred years to the lead up to the 500th anniversary, when in 1989, demonstrations began to emerge. In Denver, Colorado, 200 American Indian Movement members poured animal blood on the statue of Columbus. Interestingly, that same year, a national “Columbus Quincentennial Symposium” at the Eldorado Hotel in Santa Fe featured speakers who called into question the celebrations based on critical interrogations of more truthful accounts of the man (Columbus) and the event (1492).12 By 1990, however, a Santa Fe Quincentennial Committee planned activities locally, even as national counter protest efforts formed.13 Tibo Chávez, Jr. served as the chairman of the Commission for these celebrations and events scheduled across New Mexico included scholarly lectures, arts shows and re-enactments.

Efforts to counter the celebrations built. For some, protests against these celebrations were quiet; the pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh simply removed Columbus Day from its calendar. More demonstrative, students from the Institute of American Indian Arts staged a “die in” at the State Capital. Tonantzin Land Institute, the Southwest Indian Student Coalition and Moviemiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan of the University of New Mexico planned other protests. Perhaps the most profound response centered the value of storytelling. The Institute of American Indian Arts, in collaboration with KNME-TV, the local PBS station based in Albuquerque, along with Director Diane Reyna, produced “Surviving Columbus: The Story of the Pueblo People,” a deeply imaginative film that tells the story of the Pueblo people, including their 500 year relationship with other cultures. The film won a Peabody Award that year and resonates to this day.14

Fast forward nearly one hundred years to the lead up to the 500th anniversary, when in 1989, demonstrations began to emerge. In Denver, Colorado, 200 American Indian Movement members poured animal blood on the statue of Columbus. Interestingly, that same year, a national “Columbus Quincentennial Symposium” at the Eldorado Hotel in Santa Fe featured speakers who called into question the celebrations based on critical interrogations of more truthful accounts of the man (Columbus) and the event (1492).12 By 1990, however, a Santa Fe Quincentennial Committee planned activities locally, even as national counter protest efforts formed.13 Tibo Chávez, Jr. served as the chairman of the Commission for these celebrations and events scheduled across New Mexico included scholarly lectures, arts shows and re-enactments.

Efforts to counter the celebrations built. For some, protests against these celebrations were quiet; the pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh simply removed Columbus Day from its calendar. More demonstrative, students from the Institute of American Indian Arts staged a “die in” at the State Capital. Tonantzin Land Institute, the Southwest Indian Student Coalition and Moviemiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan of the University of New Mexico planned other protests. Perhaps the most profound response centered the value of storytelling. The Institute of American Indian Arts, in collaboration with KNME-TV, the local PBS station based in Albuquerque, along with Director Diane Reyna, produced “Surviving Columbus: The Story of the Pueblo People,” a deeply imaginative film that tells the story of the Pueblo people, including their 500 year relationship with other cultures. The film won a Peabody Award that year and resonates to this day.14

Still shot from “Surviving Columbus,” December 19, 1990

Still shot from “Surviving Columbus,” December 19, 1990Commemorative Events - Fiestas

The annual Feast Day celebrations, also known as Fiestas, provide an important point to assess how memory and community intersect, and how history is sometimes as much about forgetting as it is about remembering. To better understand these events, it is important to consider some background.

Under the Spanish empire, every community settled took the name of a patron saint. For instance, Santo Tomas Apostol de Abiquiú was the full name of the village known still as Abiquiú. This practice also included the renaming of Indigenous villages. For instance, Santo Domingo was originally known as Kewa, and San Juan de los Cabelleros was Ohkay Owingeh. Part of the work of decolonizing requires recovering and while these two villages have reclaimed their original names, celebrations continue to honor the patron saints.15

Given the long history of Catholicism in New Mexico, most feast days, defined by the centrality of these patron saints, are celebrated annually on the same date. They usually consist of a mass, vespers and a procession, followed by gatherings breaking bread in community, traditions now as common in Hispanic villages as in Pueblos. For instance, in Acoma Pueblo, the feast day honors San Esteban and in Albuquerque’s Old Town, San Felipe de Neri is at the center of a three day Fiesta.

The Fiestas de Española and Santa Fe are the primary focus of the following assessment, along with a glimpse at the Fiestas in Taos.

Española Fiesta

The annual event known as the Fiesta del Valle de Española celebrates the Spanish colonial founding of New Mexico and the establishment of the “first European Capital” of New Mexico on July 11, 1598. As articulated in the Fiesta Bylaws, the purpose of the Fiesta is to specifically,“commemorate and celebrate the initial conquest of New Mexico by Captain Juan de Oñate, and the establishment of his capital at San Gabriel de Los Españoles, at the confluence of the Rio Chama and the Rio Grande del Norte.”

First presented in 1932, the event, the development of which is credited to Delfin Salazar. It struggled to gain momentum in the first three decades.16 In 1969, however, then mayor Richard Lucero and other businessmen reignited the Fiesta.

Consistent with the development of “founders’ days” in other communities across the nation, nostalgia and mythology largely defined Española’s Fiesta, along with a desire of its celebrants to secure a sense of belonging. Though Santa Fe’s Fiesta preceded Española’s, the community took the opportunity to tell an “older story,” choosing the date of 1598. This narrative allowed City officials and other promoters to claim that moment as the ‘birth,’ not only of Española, but of the very origin of the place that would come to be known as New Mexico. For those promoters, the date also predated any other European settlement in what is today called the United States. Understanding these narrative choices reveals what early twentieth century Hispanos in Española felt was critical, a sense of belonging to a place.

That this founding story excluded Indigenous communities — which were infinitely older — is also not surprising. Equally as troubling, however, was that the narrative froze time. If the metaphor of birth can be used, then everything that follows, the evolution of a being, including that of a community, is absent, failing to account for more than four centuries of history, both violent and joyful, filled with events that dramatically transformed place and people alike.

Underlying the Fiesta del Valle de Española are elements of a dominant narrative. As articulated in the Fiesta Bylaws, the purpose of the event is to preserve “the historical, cultural and faith, of the colonization [by] Don Juan de Oñate and the first families…” Understanding the core narrative and underlying symbols embedded in this purpose is critical.

Conquest and Domination: Set within the language of empire, power and dominion, by emphasizing colonization, the narrative force focuses on the concept of celebrating conquest. Taken at face value, this approach fails to recognize the harm resulting from domination, not only at the moment of the conquest, but also as a theme that resonates for many in the present. Like much of northern New Mexico, the Española Valley is beset with a multitude of challenges, economic and social. There are struggles over resources (e.g. water and land), and challenges that are often largely defined by race and class, dividing not only Native Americans from Hispanics, but rich from poor. In this way, it is hard not to see the present also reflected in a narrative pageant that celebrates the defeat and supposed supremacy of one group over another.

First Families: The concept of ‘founding families,’ is complicated in places like the Española Valley, but perhaps anywhere. Aside from the fact that this concept premises an exclusive and perhaps even elitist framework, the idea of ‘first families’ fails to account for the fact that the settlements of the Española Valley were constantly in flux and dynamic. First, the inevitable mestizaje that followed colonization resulted in generations of racial and cultural mixture realized and defined as much by amicable unions as by coercive relations.

A Contradiction in Terms: The phrase, “Where Cultures Unite,” is highlighted in the 2017 Fiesta Bylaws, though interestingly enough, is not defined anywhere in the document. Contrary to a multicultural and harmonious, place-based concept that the phrase evokes, the reality is that the Fiesta (as defined in its bylaws and as implemented) actually promotes a static, singular perspective and not a convergence of cultures. By deconstructing this phrase, it is clear that the concept draws upon the tri-cultural narrative.

1598 - An Origin Story: According to the bylaws, Fiesta is held to “commemorate and celebrate the initial conquest of New Mexico by Juan de Oñate, and the establishment of his capital at San Gabriel de Los Españoles, at the confluence of the Rio Chama and the Rio Grande del Norte.”17 While other expeditions and even attempted settlements predate this event, the expedition led by Oñate was indeed, the first to be royally sanctioned. It included 129 soldiers and several hundred colonists — women, enslaved people, children and priests. Notably, at the time, there was a politics governing the racial identities of those on the expedition that was also subject to a racial hierarchy and that culminated in the erasure of people of color, in spite of clear evidence of the colony being racially diverse.18 In the journey up the Camino Real, the expedition stopped in Pueblo communities, where Oñate proclaimed Spain’s dominion over land and people. Finally, the expedition culminated at Ohkay Owingeh, which Oñate renamed San Juan de los Caballeros, and while the party occupied the village’s dwellings, they eventually moved to a more spacious community across the river, San Gabriel. Failing to critically assess this entire narrative in the context of the domination of land and people is problematic.

El Conquistador Oñate: At the center of the Fiesta is the image of the conquistador, a product of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Fiesta, however, the symbolism is clearly defined in the person of Juan de Oñate himself, the conqueror who led the establishment of the first permanent colony into New Mexico in 1598. There is much known about Oñate, including that after accusations of excessive violence, a judge found him guilty in 1614 of cruelty, immorality and false reporting, and permanently banished him from New Mexico.19 The revival of this individual — who inexplicably is cast as a mythic founding father, bearer of culture and a symbol of memory, identity and heritage for the most vocal New Mexican Hispanos — did not occur until the 20th century, and continues to to this day.20 Romantically, he symbolizes for some an imagined and iconic point of Spanish origin and presence in the region, and yet, for others, the essence of colonial violence.

Royal Court/Stereotypical Images: Set within a hierarchy of race and class, one of the salient features of the Fiesta adopted into the pageantry is that of a representative “royal court,” including the personage of ‘La Reina,” an interesting notion, in that historically, Spanish royalty never actually visited New Mexico in the colonial period. From an equity perspective, the idea of royalty is not representative in the democratic sense. In general, the literal meaning of a royalty court is defined by a small select group of individuals whose lineage is not only one of purity, but of a sovereignty that rules over others and is often articulated as God-given. Revealing the class-based hierarchy, the so-called royal assemblage of the Española Fiesta includes militia-based conquistadores, two priests, a Native American Scout, and both Spanish and Native American Princesas.

Aside from the militaristic and aristocratic frame in which the “royal court” is portrayed, the representations in the pageant emerged as stereotypes of both Hispanic and Native Americans. Depicted as static and frozen in time, they also failed to fully capture the complexity of New Mexican identity in history or as it evolved over time; thus Native Americans can only exist as Scout or Indian Princess. The image of the Indian Scout is not only a figure that becomes incorporated in colonial enterprises, wherein a male from an Indigenous tribe is incorporated as a soldier or paramilitary operator, but also as a symbol of how conquest required both Indigenous cooperation and ultimately, betrayal to his own natal community. In terms of the “Native American Princesa,” the fact that Pueblo inclusion is only made possible within this framework of Spanish royalty is problematic. Like her counterpart, the Scout, she is also symbolic and set in a context of the historic portrayal of Native American women as either Queens or Princesses, particularly from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, by European and American artists.21 In these depictions, Hispanics also can only exist as colonial agents: the Spanish Queen and court, priests, soldiers, and conquerors, each flat and debilitating.

In addition to the overt hierarchies of race and class, a gender analysis of the design and implementation of this segment of the Fiesta reveals these portrayals are also subject to proscribed representations for men and women. Further, evaluation of the different selection processes for each of the key figures, such as for the Oñate or La Reina figures, as stipulated by the Fiesta Bylaws, only notes on a “competitive basis.” Anecdotally, however, practice suggests that the portrayal of Oñate is usually by an older man, while conversely La Reina is often played by a younger woman. Clearly the entire representation of the court is set within a patriarchal framework, also harmful for both men and women.

Responses

Resistance and response to the Española Fiesta can be traced to different periods in time.

In 2001, the Española Fiesta Council, led by youth members calling themselves, “La Verdad,” changed the title of “La Reina”22 to that of “La Señorita Valoria La Mestiza.” This shift, accordingly recognizing the area’s bloodlines, including Spanish and Indian, prompted Laura Vigil, the 24-year old who was portraying ‘La Mestiza,’ to remark, “We’re all mixed.” According to media coverage, Vigil “wore a simple white peasant blouse with matching skirt and silver and turquoise crown.” The position reverted two years later back to ‘La Reina.’ Interestingly, that same year, the Council stripped Oñate of a traditional sword and battle gear.”23

In a 2014 opinion piece published in Green Fire Times, historian, Dr. Matthew Martinez highlighted the banishment of Oñate, and encouraged the Council to consider his exile as an important feature of the Fiesta.

In 2017, in an unprecedented act of humility, Ralph Martinez, who was portraying Oñate, participated in the Fiesta of neighboring Santa Fe, and walked with Dezmund Marcus, who was portraying the Native Scout; and without armor, including a sword, they both knelt to pray “in solidarity with Indigenous brothers and sisters” toward “promoting unity.” In another symbolic act, Martinez also helped plant trees at the Tewa Women United’s Healing Food’s Oasis.

The following year, the newly elected mayor of Española, Javier Sánchez, appointed a new Community Relations Commission (CRC), to which I served as an advisor. Tasked with altering the town’s July Fiesta celebration, the establishment of the body drew inspiration from critiques of the glorification of conquest and domination of Pueblo peoples. Charged with working to navigate tensions resulting from historic trauma, the CRC also was to identify opportunities to celebrate the community more authentically.

The City also dissolved its legal and administrative operational obligations associated with Fiesta, resulting in some members of the community creating a nonprofit 501C3 to continue the ‘Oñate themed’ Fiesta. These new organizers announced that though Fiesta would not take place in 2018, they intended to continue the event in the future as it has been presented in the past.

The City of Española also transitioned, and in July 2017 presented, “Ferias de Española,” an event without the colonialist flair intended to unite the community. Officials, whose courage is to be applauded, include Roger Montoya and Ralph Martinez.

In 2001, the Española Fiesta Council, led by youth members calling themselves, “La Verdad,” changed the title of “La Reina”22 to that of “La Señorita Valoria La Mestiza.” This shift, accordingly recognizing the area’s bloodlines, including Spanish and Indian, prompted Laura Vigil, the 24-year old who was portraying ‘La Mestiza,’ to remark, “We’re all mixed.” According to media coverage, Vigil “wore a simple white peasant blouse with matching skirt and silver and turquoise crown.” The position reverted two years later back to ‘La Reina.’ Interestingly, that same year, the Council stripped Oñate of a traditional sword and battle gear.”23

In a 2014 opinion piece published in Green Fire Times, historian, Dr. Matthew Martinez highlighted the banishment of Oñate, and encouraged the Council to consider his exile as an important feature of the Fiesta.

In 2017, in an unprecedented act of humility, Ralph Martinez, who was portraying Oñate, participated in the Fiesta of neighboring Santa Fe, and walked with Dezmund Marcus, who was portraying the Native Scout; and without armor, including a sword, they both knelt to pray “in solidarity with Indigenous brothers and sisters” toward “promoting unity.” In another symbolic act, Martinez also helped plant trees at the Tewa Women United’s Healing Food’s Oasis.

The following year, the newly elected mayor of Española, Javier Sánchez, appointed a new Community Relations Commission (CRC), to which I served as an advisor. Tasked with altering the town’s July Fiesta celebration, the establishment of the body drew inspiration from critiques of the glorification of conquest and domination of Pueblo peoples. Charged with working to navigate tensions resulting from historic trauma, the CRC also was to identify opportunities to celebrate the community more authentically.

The City also dissolved its legal and administrative operational obligations associated with Fiesta, resulting in some members of the community creating a nonprofit 501C3 to continue the ‘Oñate themed’ Fiesta. These new organizers announced that though Fiesta would not take place in 2018, they intended to continue the event in the future as it has been presented in the past.

The City of Española also transitioned, and in July 2017 presented, “Ferias de Española,” an event without the colonialist flair intended to unite the community. Officials, whose courage is to be applauded, include Roger Montoya and Ralph Martinez.

Fault lines remain however, particularly as the new group is determined to re-ignite the Fiesta as it has been celebrated for the past several decades.

Santa Fe Fiesta-Entrada

The annual Fiesta de Santa Fe is a series of events, including an historical enactment invented in the early twentieth century which become increasingly controversial over the past decade. These events follow a call for applications for candidates to portray the figures of the historical seventeenth century governor, Diego de Vargas and a wholly imagined figure of the fiesta queen, “La Reina de La Fiesta.” The Fiesta begins in June with a week of Catholic masses, as noted in the official schedule, in “honor of Don Diego de Vargas’ request for a special intercessory grace upon his arrival in 1692,” and culminates with three days of events in September, including up until recently, the “Entrada de Don Diego de Vargas.”24 The Fiesta elicits multiple sentiments across the community, including one of the only moments throughout the year when generational residents of Santa Fe gather in the plaza, a space that has dramatically shifted in the past century to reflect the impact of gentrification and displacement.25 For this group of Hispanos, the plaza in particular, though the east side of Santa Fe generally, represents a story of loss and struggles over power, resources and values. So for one point each year, the presence of people from the community in that space, as opposed to tourists on the plaza, is symbolic.

Yet, for others, the Entrada is an unconscionable celebration of patriarchy and colonialism, at the heart of an invented tradition. In spite of the sense that resistance to the event is new, tensions have actually existed for decades and have continued to escalate.

To understand the significance of the controversies associated with contemporary Fiesta, it is necessary, however, to look more closely at both the historical accounts it represents and the arc of its own creation, through its evolution, to the present moment. The origin can be traced to an idea first conceived when twelve men, friends and admirers of the recently deceased Governor Diego de Vargas, gathered in Santa Fe on September 16, 1712. With recollections, more nostalgic than historical, they noted their purpose was “recalling how this Villa [of Santa Fe] had been conquered on the fourteenth day of September of the past year of sixteen hundred and ninety-two by the General Don Diego de Vargas.”26

Before analyzing 1712, it is important to contextualize first, the moment of 1692. The goal of the de Vargas expedition, as with other previous expeditions and others that would follow, was to re-conquer the land and lay claim to it for a distant king, an ideology based on relations of rule defined by power and politics. The articulation of the Act of Possession at every Pueblo, the thousands of souls absolved and the 969 children baptized — according to de Vargas’ report to his superiors — all must be considered within the larger frame of colonialism.27 History is power and in 1692, the court chronicler, Carlos Siguenza y Gongora, charged with recounting the campaign in detail, celebrated the reconquest taking place “without wasting a single ounce of power or unsheathing a sword . . . .”28

Understanding the power of history and memory is also probably what most defined that cold rainy day in in Santa Fe in 1712. Even though most of the men gathered then had lived through some of that history, their recollections were as much defined by forgetting as remembering, a selective storytelling. First, focusing on the 1692 description as “bloodless” implied acceptance, and was perhaps the first moment when the notion of harmonious cultures began, today an ideology that is often set in the late nineteenth century. Second, because those gathered did not choose the date of the Villa’s Spanish settlement in 1610, the salient moment was re-conquest, perhaps due to their status as new recruits who had arrived in New Mexico with the de Vargas expedition. Third, the men choose not to acknowledge the seven decades leading up to the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, a definitive experience no matter the perspective, including for two of the assembled, Antonio and Salvador Montoya, whose families had survived that rebellion. Finally, and most notably, as priest-historian Fray Angélico Chávez mused in 1953, evidently these men, “wished to ignore [the] second and more important Entrada,” the one that took place in 1693.29 That event was far from bloodless; eighty-one Pueblo people died, and of the over four-hundred that surrendered, all were sentenced to ten years of servitude among the Spaniards.30 The conquest and resistance did not end with this 1693 entrada either; the reconquest, in many ways would be more a process than a singular date, yet still marked by all of the elements that characterize war in a colonial setting, including violence, cooperation, and resistance.31

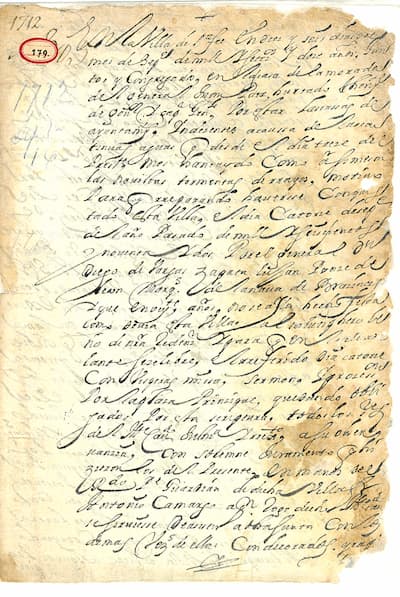

Reconquest Proclamation, order obligating the citizens of Santa Fe to celebrate “en adelante el dia de Septiembre” of each year as the anniversary of the re-conquest of the said Villa by Diego de Vargas, September 16, 1712, Spanish Archives of New Mexico II, # 179.

By the conclusion of the 1712 gathering, a decree, called for a future commemoration to be held on the sixteenth of September with “Vespers, Mass, sermon, and a procession through the Main Plaza… in honor of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross,” to be “celebrated for all time.”32 Given the centrality placed in the icon of ‘La Conquistadora,’ it is notable that nowhere in the proclamation is this figure mentioned by name or otherwise in the 1712 decree.

Reconquest Proclamation, order obligating the citizens of Santa Fe to celebrate “en adelante el dia de Septiembre” of each year as the anniversary of the re-conquest of the said Villa by Diego de Vargas, September 16, 1712, Spanish Archives of New Mexico II, # 179.

By the conclusion of the 1712 gathering, a decree, called for a future commemoration to be held on the sixteenth of September with “Vespers, Mass, sermon, and a procession through the Main Plaza… in honor of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross,” to be “celebrated for all time.”32 Given the centrality placed in the icon of ‘La Conquistadora,’ it is notable that nowhere in the proclamation is this figure mentioned by name or otherwise in the 1712 decree.

Contrary to what is often depicted by the Fiesta Council, and as many may believe, Fiesta is not an uninterrupted commemoration from 1712 to the present. The myth began as early as 1953, when Fray Angélico Chávez conjectured that it may have actually “only been observed in that year of 1712” though perhaps as long as its key author, Juan Páez Hurtado, was alive.33 Indeed, though civil and ecclesiastical authorities in New Mexico were meticulous record keepers, there is no known documentation reflecting the occurrence of Fiesta in Santa Fe following this initial date in the colonial period. Interestingly enough, under Mexican rule, there is a 1844 call for celebrating Mexican Independence, coincidently on the same date of the 1712 gathering — September 16th — to coincide with Mexican Independence in 1821, though there is no mention of the de Vargas commemoration at all, further proving that it was not being observed.34

In reality, while there is no record of the observance of Fiesta in the fashion called for in the 1712 proclamation, it could be said that Catholic celebrations inevitably did take place, including the observance of Corpus Christi and veneration of La Conquistadora. Santa Fe was originally, after all, a distinctively Catholic locale and given the centrality of the church, there is no reason to believe that some religious ceremonies did not take place aligned to liturgical calendars. While there is no evidence of the celebration of re-conquest after 1712, the concept does seem to be recovered and reinvented as pure pageantry in the late nineteenth century. As noted earlier, the introduction of the pageant of conquistadores — specifically Coronado — is first accomplished with the Tertio-Millennial Exposition in 1883, and in 1893, at the 200th Anniversary of the 1693 Re-conquest, the city’s residents are introduced for the first time to the figure of de Vargas, if not in a pageant, certainly in print.35

The Santa Fe Fiesta as we know it today was the brainchild of Episcopal minister, James Mythen. The historical enactment where a man portrays Diego de Vargas, which is core to the entrada, does not actually get presented to the public until 1911, when the idea of modern Fiesta is first introduced. The invention reflected a growing national trend in that era of costumed historical vignettes and theatricality that swept across the United States, as well as civic leaders looking to increase tourism to the city.

1926 Santa Fe Fiesta “Official Program” cover.

In subsequent decades, the Fiesta would continue to evolve under the leadership of Edgar Hewett, the founder of the Museum of New Mexico, and others as well, who upon arriving in Santa Fe, began a gradual reimagining that idealized a mythic past, place and people at the expense of the actual complexity of the population and their experiences. While other scholars tracing the history of the Santa Fe Fiesta have analyzed in some depth the evolution of these event in its first few decades especially, suffice to say that it is a story of politics, perspectives on race and class and above all, a contest of wills, primarily of men and their institutions.36

1926 Santa Fe Fiesta “Official Program” cover.

In subsequent decades, the Fiesta would continue to evolve under the leadership of Edgar Hewett, the founder of the Museum of New Mexico, and others as well, who upon arriving in Santa Fe, began a gradual reimagining that idealized a mythic past, place and people at the expense of the actual complexity of the population and their experiences. While other scholars tracing the history of the Santa Fe Fiesta have analyzed in some depth the evolution of these event in its first few decades especially, suffice to say that it is a story of politics, perspectives on race and class and above all, a contest of wills, primarily of men and their institutions.36

In tracing the origins of the Fiestas, particularly the definitive decade of the 1920s, historian Charles Montgomery notes succinctly that the “Santa Fe Fiesta was born of both Hispano-Catholic memory and Anglo contrivance.”37 Though published in 1976, Ronald L. Grimes’ Symbol and Conquest: Public Ritual and Drama in Santa Fe, an anthropological analysis of the Fiestas, particularly in the fifth, sixth and seventh decades of the twentieth century, remains one of its most in-depth studies of Fiesta. His analysis includes the Fiesta’s organizational structures and their intersections, at least as they existed in the 1973 — civic (the Fiesta Council); religious (the Co-fraternity of La Conquistadora, 1770s-1846; 1956); governmental (the City Council) and ethno-civic-religious (the Caballeros de Vargas). Although Grimes notes the challenges faced in locating the scripts for the Entrada, which he notes, “are carefully guarded by the Caballeros,” his analysis includes review of at least two, one written in 1958 and the other in 1967, the latter of which was slightly modified in the 1973 performance.38

In order to understand contemporary Fiesta, however, and the growing protests around it, it is necessary to examine even closer the existing core narratives and embedded underlying symbols. While the scripts have varied over time, the one used most recently is defined by six salient moments in the re-enactment: 1) Civil Act of Possession Articulated; 2) Religious Act of Possession Articulated; 3) Pardon of Pueblo Indians Articulated; 4) Baptism of Pueblo People; 5) Articulation of the Fiestas for all Times; 6) All asked to Venerate and Kneel before Cross. The Entrada also is based on the following core elements:

Conquest and Domination: One of the primary issues for contemporary observers is the startling celebration of the defeat and supposed supremacy of one group over another. Set within the language of empire, power and dominion emphasizing colonization, the underlying story and narrative force the commemoration on of conquest. As Grimes argues, “what occurred [in 1692] may have been bloodless, but it was still a conquest.”39 Taken at face value, this concept fails to recognize the harm that comes from domination, not only at the moment of conquest, but as a theme that resonates for many witnessing the pageant. There are living communities that upon experiencing this witnessing, internalize the story of defeat. Although the story already establishes the divide between Native Americans and Hispanos, the reaction and impulse to potential solutions is also based on this divide, though the reality is that this is much more complicated that these binaries allow. So, anyone who is witnessing and participating, is, in the end, impacted by that story, including Native Americans and Hispanics.

1692 - A renewed origin story: Although this narrative of different periods (Native American, Spanish, Mexican and American) is part of a play in progress that is included early on, it gradually evolves to focus on the singular date of 1692. As noted previously, this focus is incongruent with the actual history. Living history means learning from it. If the goal is to reveal the challenges of the last few decades of the seventeenth century, it hold lessons of clashes between cultures as well as a cooperation.

El Conquistador de Vargas: At the center of the Fiesta is the symbol of ‘the conquistador,’ a product of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the Fiesta, however, the symbolism is clearly defined in the person of Vargas himself, the man who is credited with re-establishing the Spanish colony, following the Pueblo Revolts of 1680 and 1696. Unlike the figure of Oñate, Vargas was not tried by his peers for crimes of excessive violence, though he was placed under house arrest for nearly three years, accused by the six-member Santa Fe cabildo of misappropriation of funds and fomenting Indian resistance. Ultimately released and exonerated from and even re-appointed as Governor of New Mexico in 1703, Vargas died in Bernalillo in 1704. The ways in which he would be remembered in many ways reveal less about him and more about distinctively twentieth century memorials, including a shopping mall. None would glorify and mythologize the man more, however. than the impersonations that would come more than two centuries later.

The list of those portraying de Vargas is revealing https://www.santafefiesta.org/history-of-fiesta-de-santa-fe/. Even in its early inception, those portraying de Vargas, like thirty-three-year-old George Washington Armijo, who represented the most elite Hispanos in the region. Although he is listed as an early portrayer of de Vargas, the first who plays him as part of Fiesta in 1921 is local resident and Anglo, Emory Moore. For many, the position would also come to serve as a virtual stepping stone for Hispanos aspiring to enter into the civil activities of the City, including politics.

The selection process for candidates wishing to portray this conquistador would be narrowed over time and would require the following, as taken directly from a 2018 call for candidates: must be of Spanish descent and have a Spanish surname; must speak Spanish effectively; must have been born in the State of New Mexico and must be a Santa Fe County resident for a minimum of five (5) years; and must be at least between the ages of 21 and 50 years old

Royal Court: Set within a hierarchy of race and class, one of the salient features of the Fiesta is that of a “royal court” — though no member of the Spanish royalty ever actually visited New Mexico in the colonial period — including the personage of ‘La Reina,” first introduced in Santa Fe in 1927.. From an equity perspective, the idea of royalty is not representative in the democratic sense. In general, the literal meaning of a royalty court is defined by a small, select group of individuals whose lineage is not only one of purity, but of a sovereignty that rules over others and is often articulated as God-given, thus revealing class-based pretensions.

The selection process of the Queen requires the following: must be of Spanish descent and have a Spanish surname; must speak Spanish effectively; must have been born in the State of New Mexico and must be a Santa Fe County resident for a minimum of five (5) years. There are two key differences from the selection process for the de Vargas character. First, unlike the age of the conquistador, who can be up to 50 years old, the Reyna must be between 21 and 35 years old. While there is also no requirement noted for de Vargas in terms of marital status or virginity, for the candidates for Reyna, they must “never [have] been married, nor shall she do so throughout her entire reign,” nor they “shall not have any children, nor shall she become pregnant throughout her entire reign.”

Stereotypical Images: Aside from the aristocratic frame in which a military and “royal court” is portrayed, the representations in the pageant emerge as stereotypes of both Hispanic and Native Americans, in which people are not only depicted as static and frozen in time, but that also fail to fully capture the complexity of New Mexican identity in history or as it evolved over time. In this way, Native Americans can only exist as Scout or Indian Princess. The image of the Indian Scout is not only a figure that comes to be incorporated in colonial enterprises, wherein a male from an Indigenous tribe is incorporated as a soldier or paramilitary operator, but also a symbol of how conquest required both Indigenous cooperation and ultimately, betrayal to his own natal community. In terms of the “Native American Princesa,” it is problematic that Pueblo inclusion is only made possible within this framework of Spanish royalty. Like her counterpart, the Scout, she is also symbolic and set in a context of the historic portrayal of Native American women as either Queens or Princesses, particularly from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, by European and American artists. In these depictions, Hispanics also can only exist as colonial agents: the Spanish Queen and court, priests, soldiers, and conquerors, each flat and debilitating. These offensive portrayals erase entire cultures, collapse others, and fail to account for the ethnic mixtures resulting from Indigenous, European and African cultural convergence in New Mexico history.

Responses

For years, there was a resistance to the Fiesta Entrada that has only continued to gain momentum. Protests that could have easily escalated into a riot defined the 2017 Fiestas. Over 100 individuals, including members of The Red Nation, an Albuquerque-based Indigenous rights group dedicated to the liberation of Indigenous people, and the University of New Mexico’s Kiva Club, encountered a flank of police on the ground and on surrounding rooftops, culminating in eight arrests, though charges were eventually dropped. For several months since that clash, as national news featured these events and the growing antagonism, a broad network of supporters calling for the abolishment of the Entrada has taken place. This included the All Pueblo Council of Governors (APCG) passing Resolution No. APCG 2017-20 on December 14, 2017 that outlines a “conceptual framework” of action steps toward reconciliation.

Though it may seem as if resistance to Fiesta is new, in reality, it has long reflected the continued evolution of the modern Fiesta in the twentieth century. In 1963, following internal disputes with the Fiesta Council, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe announced it would withdraw its participation in Fiesta, though three years later it was reaffirmed. Forty years before the 2017 APCG Resolution, in 1977, the All Indian Pueblo Council expressed their disapproval of the re-enactment of the Entrada. A letter from Gilbert Valdez, chairman of the Fiesta Council, requesting that Native American vendors be prohibited from selling underneath the portal during the Fiesta elicited the response. Sparking a reaction that led to the AIPC voting to support a boycott of Fiestas, the communication also served as a catalyst to begin planning efforts for a 300th anniversary of the Pueblo Revolt.40 Chairman of the AIPC, Delfin Lovato, illuminated a simmering reality when he noted, “We go to Fiesta, not because we want to participate in the Fiestas, but as a matter of economic necessity. I think I speak for 99% of Pueblo People when I say they think of the Fiesta about the pageantry about the so-called conquest as a farce anyway.”41

Since 1977, resistance and response has ebbed and flowed, but one of the most incisive responses came from the intersection of arts, technology and history in 1992. Thanks to the skill and production of Jeanette DeBouzek and Diane Reyna, their 1992 production of Gathering Up Again: Fiesta in Santa Fe frames the imperative of perspective in focusing on three individuals participants. Although the film is now over two decades old, it continues to serve as important window into this event.42

The dust that the Santa Fe Fiesta raises annually actually never fully settles, and yet the tensions that have continued to escalate have begun to feel much heavier than dust. In fact, no single metaphor fully captures the complexity and contest over memory that is played out year after year in terms that are imagined and symbolic and yet manifest in real spaces and across socio-political relations. In recent years, the Entrada has been justified in the name of tradition, though it is not actually grounded in the full history and wisdom of the people it allegedly represents.

In the midst of the recent activism to end the Entrada, I was invited to participate in dialogues with the All Pueblo Council of Governors, the Catholic Church/Archdiocese of Santa Fe and the Office of the Mayor, City of Santa Fe, focused on addressing the harm caused by the Entrada. In 2018, these initial conversations expanded to include formal meetings with the leadership of Santa Fe Fiesta Council and the Caballeros Vargas, the entity responsible for the Entrada. This collaboration — which took considerable courage and leadership and protests spearheaded by many Indigenous and Chicano women and men — based on face-to-face respectful and constructive dialogue over several months, culminated in the discontinuation and complete transformation of the Fiesta. My engagement began when the former Governor of Cochiti Pueblo, Regis Pecos, asked me to accompany him to a meeting with the Archbishop John Wester, which evolved into meetings with Mayor Javier Gonzales and presentations before the All Pueblo Council of Governors. Concomitantly, President of Caballeros de Vargas, Thomas Baca-Gutierrez, sent letters to all Pueblo governors noting, “It is my wish and my hope that I can sit down with you (and all the other Governors as well) to explore ways that we can peacefully celebrate our blended cultures and traditions of unity.” The courage of President Baca-Gutierrez continued with the next mayor Santa Fe, Alan Webber.

The Santa Fe Fiesta Council and the Caballeros de Vargas voted to discontinue La Entrada in 2018, and for many Hispanos in Santa Fe, the end of Entrada signaled another loss. While this change could have been a starting point for deeper engagement work, recognizing that reconciliation is a process, it was not. The opportunity to begin to reimagine and develop a new tradition, a new event to replace the old, remains imperative; and until then, wounds remain.

Taos Fiesta

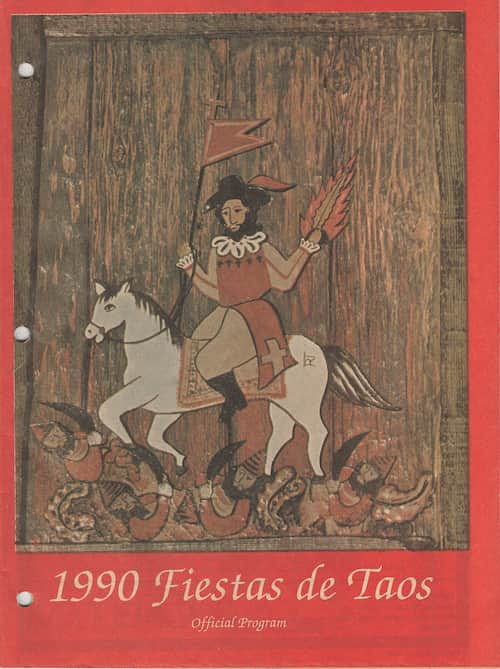

Like the Española and Santa Fe Fiestas, the Fiesta of Taos has long functioned as an event reflecting a romanticized and mythic sense of place, people and the past. Its gradual evolution also reveals how space and event function as important arenas in the struggle over values, power and the politics of representation and belonging. A product of the early twentieth century, the evolution of Fiesta, however, began at the turn of the century when town merchants recognized the Taos Pueblo feast day could be leveraged. While ceremonies at the pueblo had long coincided with different calendars and relationships, synchronicity and a cultural braiding included the incorporation of the feast day that was superimposed in 1619 when Spanish clergy built the first mission church, named for San Geronimo, the fourth century patron saint known as a historian and writer.

In 1902 a flyer promoted a three-day schedule for “San Geronimo Feast and Taos given in the old and Quaint Town of Taos,” and for more than two decades, celebrations complemented the pueblo’s feast day. By the 1930s, the impetus to create a separate festival that capitalized fully on the summer tourism took hold. Anthropologist and Taos native, Dr. Sylvia Rodriguez, completed the most in-depth research about the invented Taos Fiesta, particularly regarding power and social relations, important not only for understanding Taos specifically, but other Fiestas as well. She traces the festival from, “its invention by an elite group of Anglo boosters in the 1930s, to its control by a select Hispanic fiesta council in the 1990s.” Dr. Rodriguez also analyzes the development and contestation of community memory deeply embedded in the celebration, including how issues of identity, language, gender and race have, and continue, to play in both the programming and in the politics of its production.43

At the symbolic level, the early 1930 reinvented Taos Fiesta centered two patron saints, Santa Ana and Santiago.44 Santa Ana, recognized as the grandmother of Jesus Christ, was the mother of the Virgin Mary. Santiago, or the apostle James, came to be widely accepted as the patron saint of Spain in the seventeenth century, though Pope Clement XIII removed the designation in 1760, naming him patron of Spaniards.45

The reverence to Saint James — also known as Santiago Matamoros, Saint James the Moor-slayer — sprung from legend, where he is said to have miraculously appeared at the Battle of Clavijo, helping the Christians conquer the Muslim Moors. Historian Jean Mitchell-Lanham has noted, “While this event [itself] is based on legend, the supposed battle has provided one of the strongest ideological icons in the Spanish national identity.”

The reverence to Saint James — also known as Santiago Matamoros, Saint James the Moor-slayer — sprung from legend, where he is said to have miraculously appeared at the Battle of Clavijo, helping the Christians conquer the Muslim Moors. Historian Jean Mitchell-Lanham has noted, “While this event [itself] is based on legend, the supposed battle has provided one of the strongest ideological icons in the Spanish national identity.”

Drawing upon Saint James is not new to New Mexico. In an actual event, as part of the reconquest of Santa Fe in 1693, as the Spanish forces began the battle against Puebloan people, according to historian John L. Kessell, “they yelled the Santiago and charged.”46 The leader of the charge, Diego de Vargas, himself a member of the military Order of Santiago, had come from a long line of knights of Santiago.47 In contrast to the way in which Saint Jerome is represented, as healer and writer, the iconography that most defines Saint James is associated with Spanish colonization and thus is almost always depicted in the militaristic terms of the conquistador. That civic leaders in Taos choose this icon is perhaps intentional, particularly in its association with Spain and with conquest.

Conclusion — Time

More commemorative events will take place. As humans, we seem to have a propensity to celebrate and to remember our past. The question is what do we remember and celebrate? There are moments like 1680 that are the reverse of celebrating colonialism, but instead, the resistance to it. The year 2030 will mark the 350th anniversary of the Pueblo Revolt. It is a historically important event, perhaps not fully recognized for its significance. Toward a heightened consciousness and a reversal of perspective, what would it look like if government entities or private organizations began to design and organize an event with the same interest and investment that characterized celebrations of conquest? The Pueblo Revolt represents for some one of the first and greatest revolutions and a points of resistance to Spanish domination, while for others, it represents the death of ancestors, an interruption and loss. But as for any commemoration, it is important to trace context and what follows. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 rewrote Spanish-Pueblo policy and while subsequent centuries were not without contention and violence, it dramatically and positively shifted those relationships. The“1837 Rebellion of Rio Arriba,” also marked a cooperative effort of cross-cultural convergence centering a resistance to a common enemy, an event that has unfortunately been largely forgotten.

More than a focus on singular events, however, the question before us is, how can commemorations of the past occur within a de-colonial framework, if at all? How do we recognize the complexity of history to avoid further replicating the harms that come from representing it? Above, all, how do we ensure that what is celebrated is truthful and raises all voices? As suggested earlier, there is another set of events that merit attention in this work of decolonization that also are based on singular dates, though they are cyclical and everyday: a harvest, the cleaning of a ditch or the daily gathering around a kitchen table, all offer opportunities for conversations about the future.

Notes:

Charles Montgomery, The Spanish Redemption: Heritage, Power, and Loss on the New Mexico’s Upper Rio Grande. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, pp. 7-8. ↩︎

The Santa Fe Tertio-Millennial Anniversary Association was comprised of a Board of Directors, including W. W. Griffin, L. W. Bradford Prince, Adolph Seligman, Arthur Boyle, Charles W. Greene, Solomon Spiegelberg, E. L. Bartlett, W.v. Hayt, W. T. Thorton, A. Staab, Lehman Spiegelberg and Romulo Martinez, the sole native-born New Mexican. ↩︎

Ibid, Montgomery, pp. 93-97. ↩︎

See Wayne Mauzy, “The Tertio-Millennial Exposition,” El Palacio 37 (24) december 1934, pp. 185-99. ↩︎

As the director of the Tourist Bureau, which was promoting the newly established tagline for New Mexico, “Land of Enchantment,” noted, “Coronado was unsuccessful in his search [for gold], but the celebration that honors his journey in 1940 should mean gold for New Mexico.” Even if not completely financially successful, there was an increase in visitors. By 1935, visitorship reached a zenith of 2.7 million, four times the state’s population. Mary Irene Severns, “Tourism in New Mexico: The Promotional Activities of the New Mexico State Tourism Bureau, 1935-1950” (Master’s thesis, University of New Mexico, 1951). 1-77. ↩︎

CCC-RC. Fergusson, “The Coronado Cuarto Centennial,” 67-68. ↩︎

Rayford W. Logan, “Estevanico, Negro Discoverer of the Southwest: A Critical Reexamination,” Phylon I; 4 (1940), 305-314. ↩︎

A.L. Campa, “The New Generation,” “Juan de Onate was Mexican: The Coronado Cuarto Centennial and the ‘Spaniards,’” and “Our Spanish Character,” in Arthur L. Campa and the Coronado Cuarto Centennial, ed. Anselmo F. Arellano and Julian Josue Vigil (Las Vegas, New Mexico: Editorial Telarana, 1980), 26, 34035, 43-44. ↩︎

El Taoseno, April 17, 1940, as cited in Sylvia Rodriguez, “The Taos Fiesta: Invented Tradition and the Infrapolitics of Symbolic Reclamation,” Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring, 1997), pp. 37. ↩︎

Taos Review, June 6, 1940 as cites in Rodriguez, p. 37. ↩︎

Las Vegas Free Press, Las Vegas, New Mexico, May 20, 1892. ↩︎

Robert Mayer, “Goodbye Columbus,” Santa Fe Reporter, October 19, 1989, p. 9. ↩︎

Clay Evans, “Two Views of the Columbus Voyage,” Santa Fe Reporter, December 26, 1990, p. 23. ↩︎

To see film: https://www.pbssocal.org/programs/surviving-columbus/surviving-columbus-h5sfei/ ↩︎

In 2005, officials reclaimed the name of Ohkay Owingeh and the village named in the 17th century as Santo Domingo officially changed its name to Kewa Pueblo in 2009, altering its seal, signs and letterhead. ↩︎

See Robert Robert A. Naranjo, “History of the Fiesta del Valle de Española y Oñate,” http://valleydailypost.com/history-fiesta-del-valle-de-espanola-y-onate. ↩︎

See Fiesta del Valle de Español, Chapter 45; Bylaws of the Fiesta del Valle de Española, passed, approved and adopted by the Governing Body of the City of Española, March 28, 2017. ↩︎

In her writing and research, historian Martha Menchaca has noted that there was a racial politics to the settlement of New Mexico, wherein detailed information was specifically recorded on White soldiers, while there was concerted erasure of people of color on the expedition. In spite of the erasure, the registries actually reveal that the most of the colonists were not actually Spanish born peninsulars. These records also give us a glimpse of a few of the women, another category of individuals that is often erased in these early records. See Martha Menchaca, Recovering History Constructing Race: The Indian, Black and White Roots of Mexican Americans. (University of Texas Press: Austin, 2001, pp. 81-88. ↩︎

Marc Simmons wrote the biography of Oñate, and though it lends itself to a more positive than critical assessment, Simmons does document (without citation) the accusations, trial and sentencing. Also included in the biography are the final years of Oñate’s life working to unsuccessfully exonerate his name. See Marc Simmons, The Last Conquistador: Juan de Oñate and the Settling of the Far Southwest, University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1991, pp 187-195. ↩︎

In 1901, poet, novelist and lawyer, Eusebio Chacón, gave a speech at a rally to protest an inflammatory article by Nellie Snyder in which she articulated her aversion to Hispano Catholicism. In the speech, Chacón not only spoke to the issue of degradation noted by Snyder, which evidently articulated a negative illustration of mestisaje (racial mixture), but countered, “No blood runs through my veins other than the one Don Juan de Oñate brought, and the one later brought by the illustrious ancestors of my name.”(En mis venas ninguna sangre circula si no es la que trajo Don Juan de Oñate, y que trajeron después los ilustres antepasados de mi nombre.”) See La Voz del Pueblo, November 2, 1901, reprinted in Anselmo Arellano, “El Discurso Elocuente Nuevo-Mexicano,” New Mexico State Records Center and Archives. ↩︎

See: http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/american-encounters/american-encounters-women.php. ↩︎

Communications with Carlos Trujillo by text took place on March 25, 2018. ↩︎

See Stone, Marissa, “Changing of the Guard: Española crowns La Mestiza,” Santa Fe New Mexican, Santa Fe, July 9, 2001, page 1. Also, editorial, “Fiesta Changes Boost Community,” Albuquerque Journal, Albuquerque, July 8, 2001, page? ↩︎

See the website for the Santa Fe Fiesta Council, https://www.santafefiesta.org ↩︎

Although tracing the changes that have taken place over the past century may be revealing, even the past 50 years illustrates how tourism, the arts, upscale dining and retail had dramatically transformed the core of Santa Fe, residents who could no longer afford to live close to Downtown moved to the outskirts. Early waves of gentrification in 1960s and 1970s were foundational in terms of the current population in the north and east sides of town, which is primarily limited to a retirement community, with 66% of residents aged 60 or over. Overall, 70% of Downtown residents are White and based on research from 2009-2013, median household income was about $60,162, higher than the Santa Fe Urban Area’s at $51,278. For more in-depth information, see Human Impact Partners, Equitable Development and Risk of Displacement: Profiles of Four Santa Fe Neighborhoods, 2015. ↩︎

See, record # 179, “Order obliging the citizens of Santa Fe to celebrate “en adelante el dia de Setiembre” of each year as the anniversary of the re-conquest of the said Villa by Diego de Vargas, September 16, 1712’ Spanish Archives of New Mexico, Vol. II, ed. R. E. Twitchell. Torch Press, 1914. ↩︎

See Diego de Vargas to Conde de Galve, Santa Fe, 16 Oct. 1692, Archivo General de la Nación, HIstoria 37: 6, Mexico City, Mexico and The Mercurio Volante of don Carlos de Siguenza y Gongora: An Account of the First Expedition of don Diego de Vargas into New Mexico in 1692, trans. Irving A. Leonard (Los Angeles, 1932), both cited in John L. Kessell, Remote Beyond Compare: Letters of don Diego de Vargas to His Family from New Spain and New Mexico, 1675-1706. ↩︎

Following the first of de Vargas’ visits back into New Mexico, the event was described in a news bulletin as having taken place “without wasting a single ounce of power or unsheathing a sword. . .” See L. Kessell, Kiva, Cross and Crown: The Pecos Indians and New Mexico, 1540-1840. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1990, p. 254. ↩︎

For translation of the proclamation and commentary, see Fray Angélico Chávez, “The First Santa Fe Fiesta Council, 1712,” New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. XXVIII, No. 3, July 1953) pp. 183–85. ↩︎

Kessell, Ibid, p. 262. ↩︎

There was, in fact another, perhaps lesser known, revolt, but the 1696 Pueblo Revolt, was according to J. Manuel Espinosa, the “last serious effort by the Pueblo Indian medicine men and war chiefs, and their embattled warriors to drive out the Spanish,” and the Spanish victory was the final stage in securing the reconquest and the permanence of the Spanish settlements in northern New Mexico.” See The Pueblo Indian Revolt of 1696 and the Franciscan Missions in New Mexico, trans and ed, J. Manuel Espinosa. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988, p.3. ↩︎

See Ralph E. Twitchell, Spanish Archives of New Mexico, Vol. IV. , p ↩︎

Juan Páez Hurtado died on May 5, 1724. Chávez, Ibid, p. 190. ↩︎

On July 28, 1844 Governor Martínez de Lejanza ordered that a “patriotic council” be organized in Santa Fe, in order to celebrate Mexican Independence. See Governor Martínez de Lejanza, “Acta de la instalación de la Patriótica para la celebridad del aniversario de la Independencia Mejicana en la Ciudad de Santa Fe, Capital del Departamento de Nuevo Méjico el día 16 de Setiembre, 1844.” For full proceedings of the Junta Patriotica, see MANM, Roll 37, frames 564-600. Though beyond the scope of this project, I have analyzed this event as a pivotal moment in Spanish - Ute relations, and even in the planning of this event, reveals colonial violence against indigenous peoples. See Estevan Rael-Galvez, Identifying Captivity and Capturing Identity: Narratives of American Indian Slavery In Colorado and New Mexico, 1776-1934, Ph.D Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2002, pp. 115-119. ↩︎

The New Daily Mexican ran an article on June 10, 1893, “De Vargas Vow,” accentuating the story of “when the intrepid De Vargas reconquered the Pueblo Indians that held barbaric sway in this city,” and pointed to a called the attention to their readers to the “beautiful procession which will form at the cathedral and proceed to the Rosario chapel tomorrow afternoon.” This is fully cited in Chris Wilson’s The Myth of Santa Fe - Creating a Modern Regional Tradition, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997, p. 189. According to historian Charles Montgomery, superintendent of Public instruction Amado Chavez “distributed excerpts of the Vargas diary to educators across the United States.” that same year of 1893. Montgomery, Ibid, p. 133. ↩︎

See Grimes, Symbol and Conquest; Montgomery, “Discovering “Spanish Culture” at the Santa Fe Fiesta, 1919-1936,” Chapter 4, Ibid, pp. 128- 157. ↩︎

Montgomery, Ibid, p. 129. ↩︎

Grimes, Ibid, pp. 152-212. ↩︎

Grimes, Ibid, p. 167. ↩︎

“Pueblos Vote For Boycott in Santa Fe,” Albuquerque Journal, Sept. 16, 1977. ↩︎

Indians to Sell During Fiesta,” Las Cruces Sun News, Sept. 9, 1977. ↩︎

See two articles by anthropologist Sylvia Rodriguez: “Fiesta Time and Plaza Space: Resistance and Accommodation in a Tourist Town,” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 111, No. 439 (Winter, 1998), pp. 39-56; and “The Taos Fiesta: Invented Tradition and the Infrapolitics of Symbolic Reclamation,” Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Spring, 1997), pp. 33-57. ↩︎

See Mary Montano, Tradiciones Nuevomexicanas: Hispano Arts and Culture of New Mexico. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001), p. 74. ↩︎

See Clifford J. Rogers, The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Oxford University Press. p. 404. ↩︎

Kessell, Ibid, p. 261. ↩︎

Kessell, Remote Beyond Compare, Ibid, p. 74. ↩︎